controlled

areas. They are also known as “day and night IDPs” concentrated mostly in

eastern province. They live within the district of their former residence and

sometimes have access to their property during the day.

(e) Then there are IDPs living with friends and relatives.

The main causes of displacement

of people vary from place to place and from community to community. The

displacement could be due to economic, environmental, ethnic and political

factors. Overall, the reasons for

displacement can be summarized as: First, the prolonged war has severely

affected the livelihood of the people. Apart from this, both the sides have been

deliberately targeting civilians as part of their war strategies. Neither side

takes adequate safeguards to avoid civilian causalities. Second, frequent

military operations by both the sides also causes displacement, since one is not

sure of the nature and duration of the operations and there are high chances of

causalities. For instances, the most recent military clash between the two

parties, despite the existence of the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement (CFA), around 200

odd civilians have been killed and UN agencies estimate around 2.3 Lakhs people

have been displaced from Jan-Sept 2006.

Third, the LTTE for its own long-term gains, from time to time have forced the

Muslim community living in the north to leave the area, sometimes within 48

hours. For instance, in 1990, around 90,000 Muslim residents were evicted by the

LTTE from the north, who now live in Puttalam, Anuradhapura and Kurunegala

areas. In spite of the atrocities, the Muslim community is known for taking a

neutral position in this protracted conflict. Fourth, the frequent human rights

violations by the rebels and the security forces like the harassment, arbitrary

arrest, detention, torture, sexual harassment, has also led to displacement. For

example, according to Sri Lankan Monitoring Mission (SLMM), from February 2002-

July 2006 the number of violations of the CFA committed by the GOSL and the LTTE

is around 277 and 3944 respectively.

Of these, the violation by GOSL includes the Harassment (30%), Hostile acts

against the civilian population (6.27%) and the harassment by LTTE includes 6.54

per cent. Subsequently, from time to time the LTTE’s forced recruitment of

women and children has been increasing, this has further intensified during the

current peace process. According to SLMM, the child recruitment carried out by

the LTTE alone constitutes around 47 per cent of total violations, followed by

abduction of adults by the LTTE and GOSL includes 16 per cent and 5.54 per cent.

Hence, in order to save the lives of their family members, they are forced to

flee.

Tsunami Related IDPs

The tsunami

that struck the island on 26 December 2004, in just 20

minutes it wiped away communities, cities, villages, dismember families,

destroyed the infrastructure that had been built over the years. This

tragedy

devastated the coastal island

stretching over 1,000 km which is about 70 per cent of the coastline. The

devastation was concentrated on the coast between Galle in the south and

Trincomalee in northeast. As

a result, around

two lakhs families displaced, 40,000 deaths, and

5,000

were missing

15,000 injured and many were in need of medical attention.

In addition, around 900 to 1,000 children lost their parents, and 150,000 homes,

200 of educational institutions and 100 health facilities were destroyed or

severely damaged.

Hence, the tsunami was big blow for the Sri Lankan people who were already

undergoing the scourge of ethnic conflict for more than two decades.

Against this background it is

important to compare the response of GOSL, LTTE, international community, civil

society and people towards the conflict and tsunami related IDPs.

Comparison

The tsunami tragedy appeared to

be everybody's disaster. As most of the people around the world and within Sri

Lanka assessed the damage, identified needs, and expressed sympathy/ opinions on

the progress and delivery of aid. Even the members of the Sri Lankan diaspora

came in numbers and donated huge funds to help their people.

At the same time, both the national and international media played a vital role

in highlighting the issues of tsunami affected persons. As a result, funds began

to pour, international agencies, community to certain extent was able to reach

out and meet the needs of the victims. Interestingly, people cut across

communities, accommodate their differences and put up a brave front in providing

relief and carrying out rescues operations. For example, the Buddhist monks and

Christian clergymen worked together in villages close to the southern city of

Galle. The clergyman through their network of churches was quick to receive

loads of relief and money, which they wanted to disburse through what they

called ‘inter-religious’ work. Even the temples were turned into a relief

camp.

Moreover, very surprisingly, in few areas the Sri Lankan Army (SLA) and rebels

stood side by side helping tsunami victims in the immediate aftermath of the

disaster. Thus, the positive response of people gave much needed support to the

victims of tsunami during the crisis period.

Unfortunately, this form of

public support, awareness was/is not visible when it comes to dealing with

conflict related IDPs. This is due to the ethnic polarization of people, limited

support from the international community, financial crunch, and lack of

co-ordination between LTTE and GOSL over addressing the issues of IDPs.

Subsequently, the role of media has not been encouraging as reporting of these

IDPs is considered to be unpatriotic and even media is divided on ethnic lines.

However, one of the vital limitations of media is that it has limited access to

areas were IDPs are displaced due to restriction from LTTE.

Response

of GOSL and LTTE

The response of GOSL and LTTE in

dealing with tsunami affected IDPs has been inadequate. The President Chandrika

Kumaratunga declared a State of Emergency and concentrated all powers relating

to post-tsunami relief and reconstitution in highly centralized authority. As a

result, the government was not able to fully co-ordinate and carry out immediate

relief works, due to the usual political and

administrative delays. Despite this, the GOSL offered better housing,

more relief items, utensils and more care to the tsunami victims than conflict

related families. Moreover, the financial

resources spent by the GOSL for each house of a tsunami victim are much larger

than those spent for housing programmes for conflict displaced families.

This exposed the double standard adopted by GOSL in dealing with IDPs. On the

other hand, the LTTE responded with military approach by depending upon its

cadres and Taml Rehabilitation

Organization (TRO) to carry out the humanitarian works in northeast.

Although, the tsunami caused severe destruction in the Eastern and North-eastern

coastal belt which is LTTE-held areas, as a result the GOSL did not have any

access to most of this coastal areas situated in the so-called ‘uncleared

areas’. Moreover, in January 2005, the GOSL

without consulting the affected communities had declared buffer zone policy,

i.e., zone of 100 or 200m inland from the seashore was to be kept free of

housing construction. Similarly, the LTTE also declared buffer zone of 300m

prohibition zone. This aroused panic and fear among the public who had already

lost their livelihoods.

Apart from this, the GOSL and LTTE were not able

reach an agreement for the joint management of aid, which was one of the

conditions put forward by the international donors. As a result after

must heated negotiations [six months and 13 drafts] on 24th June 2005

the GOSL and the LTTE signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for

establishing Post-Tsunami Operational Management structures (P-TOMS), also known

as Tsunami Relief council (TRC).

However, on 15 July 2005, the P-TOMS received a setback with the temporary

invalidation of the mechanism by the Supreme Court. Thus,

the GOSL and LTTE spent much of time in negotiating and settling scores than

responding to tsunami IDPs.

However, to certain extent the

response of GOSL and LTTE to conflict affected IDPs has been encouraging,

particularly since the 2002 peace process. As a result of peace talks around

380,000 people have returned since ceasefire came into existence. Moreover, by

the end of 2003, around 24,103 families were at various Welfare Centres and

there are 75,891 families outside the Welfare Centres.

During the peace talks, resolving the issue of the IDPs was given top priority,

especially at the discussions held at Thailand in October-November 2002. The

outcome of the talks led to the establishment of three sub-committees – the

Sub-Committee on Immediate Humanitarian and Rehabilitation needs in the North

and East (SIHRN). Its main functions are to identify humanitarian and

rehabilitation needs, prioritize implementation of activities, decide on the

allocation of the financial resources and also determine implementing agencies

for each of the activities. The other two sub-committees, focuses on Military

De-escalation and Normalization and Political Matters. It also was to addresses

some IDP related issues like housing in the High Security Zones (HSZ).

Apart from this, both the parties had expressed concern over the welfare

of the IDPs during all the negotiations held so far.

Apart from this, the GOSL has

intensified its efforts for the safe return of IDPs by establishing various

departments and launching programmes co-ordinated by the international

community, aid agencies and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs). For

instance, for the returning IDPs the government launched a National Framework

for Relief, Rehabilitation and Reconciliation. Along with the UN, the government

also introduced the “Donor Alert and Quick Impact Project” to assist the

returning IDPs. The Government has also launched a Unified Assistance Scheme (UAS)

for the returnees, which commenced from December 2002.

The Ministry of Rehabilitation, Resettlement and Refugees (MRRR) are involved in

finding a durable solution to the IDP problem and in initiating a comprehensive

registration of all IDPs. Subsequently, the Ministry of Eastern Development and

Ministry for Assisting Vanni Rehabilitation have undertake small-scale

self-employment and income generating projects to uplift the living standards of

the displaced families are playing a significant role.

Subsequenlty, President Kumaratunga after meeting the heads of the UN

agencies and the government officials for speedy resettlement of IDPs, allocated

a sum of Rs.10 million as an interim measure for assisting the resettlement of

the IDPs in eastern province.

In November 2005, the Mahinda Rajapakse government established Reconstruction

and Development Agency (RADA) for combining the work of the separate task forces

into one agency responsible for all reconstitution and development activities in

post-tsunami and post-conflict areas.

Subsequently, Ministry of Resettlement and the Ministry of National Building and

Development was also created. However, due to lack co-ordination among these

department, the plight of conflict related displacement is still perpetuating.

Response

by the International Community and Agencies

They have been playing a vital

role in addressing the issues of conflict related IDPs, especially during the

current no war situation, by addressing the needs of large-scale voluntary

returnees. Numerous international community through UN agencies are involved in

rehabilitation and resettlement of IDPs, such as UNHCR, ICRC, UNICEF, WFP, CARE,

UNDP, WHO, MSF and so on. All these organizations are co-ordinating with the

government, the local NGOs and among themselves for an effective implementation

of the said programmes and policies. They are involved in various activities,

like: delivery of food and non-food items; providing basic facilities like

water, clothes, blankets, mats, cooking utensils and sanitation; training of

teachers and setting up non-formal community schools for droop-outs.

They are also involved in assisting the authorities in stabilizing the situation

in IDPs areas where they have to remain in welfare centres pending return to

their places of origin; tackling epidemics, promoting female reproductive health

and establishing communication and postal service for connecting separated

families.

Other activities include implementing micro-projects conducted in co-operation

with the government and local NGO partners for the returnees; developing

framework of assistance, relief and rehabilitation of the war-affected

communities; mine awareness, assisting government in improving the health care

services and social rehabilitation of war-affected groups, particularly

children, widows and destitutes.

The response of the

international community and agencies toward the addressing the problems of

tsunami affected IDPs has been overwhelming in terms of providing aid, relief

efforts channeled through the I/NGOs and UN agencies. For instances, the UNHCR

has completed its post-tsunami role as coordinator of nation wide transitional

shelter and it ahs build more than 58,000 shelters by over 100 NGOs in November

2005.Subsequently, 4,500 transitional shelter units in northern district of

Jaffna and eastern district of Ampara has been completed.

Role

of Civil Society Organizations

The response of CSOs to the

tsunami related IDPs was effective and overwhelming than their response to

conflict related IDPs. For instances, the CSOs brought much need funds for

relief and reconstitution, which GOSL could not due to lack of progress in peace

process. As a result, the CSOs with the assistances from the foreign countries

and institutions responded immediately by providing basic needs like food,

clothes and shelter, organizing rescue operations, finding the survivors and

dead. Subsequently, many of the agencies had deployed

their staff members as well as volunteer citizens within a few hours, without

being constrained by the bureaucratic rules from the government. Subsequently,

they could also easily tap individual voluntarism and the private philanthropy

of fellow citizens.

According to Silumina,

the Sunday newspaper stated that “NGOs have taken nine out of the ten billion

foreign aid”.

This was obvious, as many foreign donors had refused at that moment to channel

funds through the government, due to the inability of the government and the

LTTE to evolve an institutional framework to facilitate a joint re-building

process. In the areas controlled by the LTTE, it was the TRO with local

partners, has been operating since 1985 and during tsunami it carried out the

relief and rehabilitation programmes. It looked after the tsunami victims

together with the Red Cross and UNICEF.

However, due to certain

loopholes among the CSOs, the funds for tsunami victims did not benefit. Such

as, most of I/NGOs were inexperienced in regional politics of aid and ethnicity

and under pressure to release their funds. Unfortunately, the relief was

concentrated only on building schools and orphanages, donating fishing boats.

One of the motives behind is to attract media attention and which will in turn

attract more funds. These measures proved to be counter-productive, according to

the fisheries experts warned that the large number of boats distributed, had

exceeded the pre-tsunami level, and this act will increase the pressure on the

limited fishing resources around the coastline.

Moreover, many local and international NGOs continue to distribute relief item,

often without even looking at how is receiving them. In addition, many of the

NGOs did know the local languages, because of which they were not able to

address the necessary needs of victims. Thus, the overall response of the CSOs

towards tsunami affected people was adequate.

Status

of Muslim IDPs

The Muslim community has been

victim of both prolonged conflict as well as tsunami disaster. Unfortunately,

neither the GOSL nor the LTTE has adequately addressed the relief and

reconstitutions programmes for this community. For example, during the tsunami

tragedy, the highest death toll was suffered by the Muslims, in particular in

the southeast, the Amparai district, which accounted for almost one third of the

overall death toll.

The Batticaloa region was one of the most affected district since 1978, as these

people were displaced more than four times since 1978. However, the state

assistance was minimal, due to inefficiency of state machinery and the weakness

of the deeply divided Muslim political leadership. Subsequently, the GOSL and

the LTTE backed TRO was concentrating on welfare of Sinhala and Tamil

communities respectively and neglecting the plight of Muslim community.

Moreover, due to lack of access by the government in the areas under the control

of LTTE, relief programmes could not reach the Muslim victims. At the same time,

neither the government controlled areas were hardly cleaned or cleared at all.

On the other hand, the Hambantota, constituency of Rajapakshe has received

adequate attention and support than any other areas in north east. Ironically,

many Muslims of northern region are still languish in refugee camps for over

fifteen years without much serious relief and rehabilitation efforts nor were

receipt of any aid given by the international community either for conflict or

tsunami related IDPs. Thus, Muslim community has been at disadvantages position

vis-à-vis other communities.

The Challenges

Although the situation

of both conflict and Tsunami related IDPs has improved to certain extent,

however there are still many challenges that have aggravated the sufferings of

IDPs. For instances: (a) the government institutions involved in relief,

rehabilitation and reconstruction of the IDPs, each of these Ministers,

departments and institutions – have different areas of responsibility,

geographical areas of coverage and work at different administrative levels

with little or no co-ordination. There is a lack of uniformity in the

distribution of compensation package, as the IDPs in the LTTE held areas have

reportedly not received any form of compensation from the TRO due to lack of

funds.

In addition to this, the study done by the Sri Lankan Human Rights Commission

has highlighted the failure of the government on various grounds such as, the

basic needs of the most vulnerable not being effectively addressed and that

their rights to life and dignity are being constantly violated. It further

stated that the government policy towards the IDPs is lacking vision and is

vague and constantly shifting. Moreover, the policy is shaped by military

factors rather than on recognition of the rights of IDPs. (b)

The prolonged use of landmines by the government and the rebels as a

defensive weapon, and their subsequent failure in taking drastic steps to

minimize the threat of mines to the civilian life has become a serious

hindrance to the safe return of refugees and displaced people. It has also

affected the various humanitarian activities carried out by the international

agencies and other NGOs. Nearly one million landmines have been laid in

war-zones, and so far only 10% of them have been removed.

In fact, reports of mine causalities have been increasing since 2002,

mostly in Vanni and Jaffna peninsula, from where most of the IDPs are

returning. Hence, handling the return of IDPs on a large scale to the

mine-infested war ridden areas would be a difficult task for the government.

(c) The quest for parity between the government security forces and the LTTE

on the HSZ has prevented the safe return of the IDPs, instead it has led to

further displacement. The LTTE has consistently demanded for the removal of

HSZ in the Jaffna peninsula, stating that IDPs cannot

return to their homes because of the Sri Lankan Army’s occupation of their

lands. The government, on the other hand, refuses to give in to the

LTTE’s demand on security grounds, and instead insists that the LTTE should

first disarm. Although the number of IDPs displaced from the current HSZ is

less, the issue of the HSZ has become a major stumbling block for implementing

various resettlement plans. (d) Lack of sustainable conditions to support a

durable return and resettlement of the IDPs has further marred the progress.

There are regular reports of extra-judicial killings, arbitrary detentions and

harassment by security forces at various welfare centres and also at

checkpoints. Even the Amnesty International has expressed concerns over the

rising incidents of rape, incidents allegedly perpetuated by police, army,

navy personnel and also by the rebels.

Moreover, the shortages of personnel, strict control of supplies and

inadequatacy of infrastructure have further severely limited the functioning

of local services, including health, education, roads and agriculture. These

factors have gone a long way in diminishing the confidence of the returning

IDPs. (e) The intensifying of violence since the CFA, i.e.,

violence between the LTTE and the government, violence within the LTTE,

violence between the LTTE and other Tamil Groups have created a violent

atmosphere in which the survival of conflict and tsunami related IDPs have

been impossible.

Thus, the need of

the hour is that GOSL and the LTTE should resume the peace talks at the

earliest and abide by the CFA. Fortunately,

the

both have agreed to do so owing

to

international pressure and condemnation of its atrocities. The donor

communities should turn their pledges into cheques and cash, so that CSOs

can

carry

out the humanitarian programmes effectively. The GOSL should also

build consensus with Sinhala hardliners like the JVP and JHU for successful

resolving of the conflict. Subsequently, GOSL should do

away with the top-down approach in conflict resolution, and

accommodate

CSOs for a sustained and lasting peace. Finally, the government,

citizens and the donor community should equally address the grievances of both

conflict and tsunami related IDPs. If

this does not happen, then plight of conflict and tsunami related IDPs would

continue.

Udan Fernando and Dorothea Hilhorst, “Everyday

Practices of Humanitarian Aid: Tsunami Response in Sri Lanka”, Development

in Practice, Vol: 16 ,

Issue: 03-04 ,

June 2006, pp.

292–302

“Sri Lanka: Imperative to respond to needs of conflict displaced”, 28

October 2005. Avaliable at http://www.refugeesinternational.org/content/article/detail/7140

Jayadeva Uyangoda ,

“Ethnic conflict, the State and the Tsunami Disaster in Sri Lanka”, Inter-Asia

Cultural Studies, Vol: 6, No.

3, September

2005, pp. 341-352

Conference Report on Researching Internal Displacement: State of the Art,

Series of Articles in Forced Migration Review, May 2003, p.34.

Internally Displaced People: A Global Survey, Second Edition (London:

Earthscan Publication limited, 2002), p.129.

How

relevant are the UN Guiding Principles for different countries in South Asia?

Nir Prasad Dahal

1. Background

The

displacement or forced migration of people within their own countries is today a

common international phenomenon. According to the United Nations Commission on

Human Rights "in more than 50 countries and practically in every world

region, more than 25 million people are actually considered as displaced people

just as a result of violent conflicts and human rights violations". This

number increases by several millions with those who have been uprooted by

natural or manmade disasters (HRWF, 2005).

Internal displacement

especially the conflict induced internal displacement is emerging worldwide as a

burning problem. Study

on forced migration is, therefore, becoming more meaningful coming upto 21st

century when incidences of war, violence and cruelty causing tremendous

incidences of internal displacement, human trafficking, human smuggling, and so

on are taking place. Estimates on number of IDPs are said to be controversial

due to debate over definitions, and to methodological and practical problems in

counting. The number of IDPs around the world is estimated to have risen from

1.2 million in 1982 to 14 million in 1986. At the end of 2001, there were

estimated to be 22 million IDPs worldwide, although this is likely to be

conservative figure. As shown by one of the studies, more than 52 countries

worldwide have been affected by the conflict induced internal displacement

causing around 25 million of people displaced internally in the form of internal

refugees[i].

Region-wise, Africa has been the most severely affected region in the world

where more than 12 million people of around 20 countries have turned IDPs

followed by Asia-Pacific, Americas and Europe where more than three million IDPs

each have been living in problems and challenges (Table 1).

Table 1: Number of IDPs

(estimates; as of end 2003 in million)

|

IDPs

|

Region

|

Countries

|

|

12.7

|

Africa

|

20

|

|

3.6

|

Asia-Pacific

|

11

|

|

3.3

|

Americas

|

4

|

|

3.0

|

Europe

|

12

|

|

2.0

|

Middle

East

|

5

|

|

24.6

|

Global

|

52

|

Source:

Norwegian Refugee Council 2004

Since

region-wise number of the countries accounting for the IDPs are 11, 4, 12 and 5

respectively for Asia-pacific, Americas, Europe and Middle East, it can be said

that conflict induced displacement has been approaching worldwide as a burning

problem.

The

internally displaced often face a far more difficult future. They may be trapped

in an ongoing internal conflict. The domestic government, which may view the

uprooted people as ‘enemies

of the state,’retains

ultimate control of their fate. There are no specific international legal

instruments covering the internally displaced, and general agreements such as

the Geneva Conventions are often difficult to apply. Donors are sometimes

reluctant to intervene in internal conflicts or offer sustained assistance.

2. Introduction to UN

Guiding Principles on Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

In

April 1998, the Representative of the UN Secretary General on IDPs presented to

the United Nations Commission on Human Rights a set of Guiding Principles on

Internal Displacement. The Commission in a unanimously adopted resolution took

note of these principles whose text is reproduced in Reading V.A (Chimni, 2000).

The Guiding Principles on Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) has included 30

principles to address the problems of IDPs and they have been divided into

introduction and other five sections: General Principles, Principles Relating to

Protection from Displacement, Principles Relating to Protection during

Displacement, Principles Relating to Humanitarian Assistance and Principles

Relating to Return, Resettlement and Reintegration.

Introduction

describes the scope and purposes of Guiding Principles. This Section stated that

the Guiding Principles address the specific needs of internally displaced

persons worldwide and they identify rights and guarantees relevant to the

protection of persons from forced displacement and assistance during

displacement and return. This section also provides the widely accepted

definition of Internally Displaced Persons (hereafter IDPs) i. e. “IDPs

are persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to

leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of

or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized

violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who

have not crossed an internationally recognized State border.”

Section

one provides general principles (Principles 1-4) in which IDPs shall enjoy the

rights and freedoms under international and domestic law as do other persons in

their country (no discrimination), these principles shall be observed by all

authorities, groups and persons irrespective of their legal status and applied

without any adverse distinction, these principles shall not be interpreted as

restricting, modifying or impairing the provisions of any international human

rights or international humanitarian law instrument or rights granted to persons

under domestic law. National authorities have the primary duty and

responsibility to provide protection and humanitarian assistance to internally

displaced persons within their jurisdiction, certain internally displaced

persons such as children, especially unaccompanied minors, expectant mothers,

mothers with young children, female heads of household, persons with

disabilities and elderly persons, shall be entitled to protection and assistance

required by their condition and to treatment which takes into account their

special needs have been included.

Section

two included the principles relating to protection from displacement (Principles

5-9). Principle 5 stated that all authorities and international actors shall

respect and ensure respect for their obligations under international law,

including human rights and humanitarian law, in all circumstances, so as to

prevent and avoid conditions that might lead to displacement of persons.

Similarly, principle 6 affirms that arbitrarily displacement must be avoided and

principle 7 provides a list of

procedural protection that must be guaranteed, including decision making and

enforcement by appropriate authorities, involvement of and consultation with

those to be affected and the provision of an effective remedy for those wishing

to challenge their displacement. Principle 8 states ‘Displacement shall not be

carried out in a manner that violates the rights to life, dignity, liberty and

security of those affected and principle 9 articulates a ‘special

obligation’ to protection against

displacement of a number of groups whose special attachment to territory has

been recognized in international law, including indigenous persons, minorities,

peasants, and pastoralists.

Section

three states the principles relating to protection during displacement

(Principles 10-23). This section

provides different rights of IDPs (i.e., inherent right to life, protection from

genocide, murder, arbitrary executions, and enforced disappearances including

abduction, detention, attacks, threatening to death, rights to dignity, mental

and moral integrity, protection to rape, mutilation, torture, cruel, inhuman or

degrading treatment, forced prostitution, slavery, sexual exploitation, right to

liberty, protection from discriminatory practices of recruitment into any army

forces, right to know the fate and whereabouts of missing relatives, the right

to an adequate standard of living, the right to recognition everywhere as a

person before the law, protection from arbitrarily deprivation of property and

possessions, right to education etc,) during their displacement. Principle 15

particularly mentions the following rights of IDPs;

a.

The right to seek safety in another part of the country;

b.

The right to leave their country;

c.

The right to seek asylum in another country; and

d.

The right to be protected against forcible return to or resettlement in any

place where their life, safety, liberty and/or health would be at risk.

Similarly,

section four included the principles relating to humanitarian assistance

(Principles 24-27). These principles particularly focused that humanitarian

assistance should be provided to the IDPs in accordance with the principles of

humanity and impartiality and without discrimination and these assistance should

not be diverted for political or military reasons. The government is primarily

responsible for providing humanitarian assistance to the IDPs, however,

international humanitarian organizations and other appropriate actors have the

right to offer their services in support of the IDPs. Persons engaged in

humanitarian assistance, their transport and supplies should be protected from

the attacks and other acts of violence. Moreover, humanitarian organizations and

actors should respect relevant international standards and codes of conduct.

At

last, in section five the Guiding Principles (Principles 28-30) provide that

competent authorities have the primary duty and responsibility to provide the

means, which allow IDPs to return voluntarily in safety and with dignity to

their habitual place of residence. Furthermore, these authorities have the duty

and responsibility to assist returned and / or resettled IDPs to recover their

property and possessions. Moreover, Principle 30 emphasizes that all authorities

concerned should grant and facilitate for international humanitarian

organizations and other appropriate actors in IDPs’ return or resettlement and

reintegration.

According

to Cohen “the Guiding Principles consolidate into one document all the

international noms relevant to IDPs, otherwise dispersed in many different

instruments. Although not a legally binding document, the principles reflect and

are consistent with existing international human rights and humanitarian law. In

re-stating existing norms, they also seek to address grey areas and gaps. An

earlier study had found 17 areas of insufficient protection for IDPs and eight

areas of clear gaps in the law. No norm, for example, could be found explicitly

prohibiting the forcible return of internally displaced persons to places of

danger. Nor was there a right to restitution of property lost as a consequence

of displacement during armed conflict or to compensation for its loss. The law,

moreover, was silent about internment of IDPs in camps. Special guarantees for

women and children were needed” (Cohen, R., 1998 Cited in Chimni, 2000).

The

Guiding Principles are soft laws and they are not legally binding, but the 30

recommendations—which

define who IDPs are, outline a large body of international law already in

existence protecting a person’s basic rights and the responsibility of states—were

designed to help governments and humanitarian organizations in working with the

displaced.

3.

Relevancy of the UN Guiding Principles for different Countries in South Asia

In South Asia, each and every

country is facing the problems of IDPs. Their situation is more vulnerable than

that of refugee because refugees are protected by international humanitarian and

human rights law but unlike the refugees they are never able to move away from

the site of conflict and have to remain within a state in which they were forced

to migrate in the first place. The following section briefly describes the

situation of IDPs of some South Asian countries and the relevancy of UN Guiding

Principles on Internal Displacement.

Afghanistan

There has been on-going

conflict in Afghanistan for the last twenty years, leading to massive

displacements both within Afghanistan, and as refugee movements, into Iran and

Pakistan. In Afghanistan, the causes of internal displacement are Soviet

invasion in 1979, start of civil war in 1993, drought and famine of 1996, US air

strikes in 2001 and anti-Pushton violence since Northern Alliance regained power

in 2001. The total numbers of IDPs is estimated as 11,60,000 persons (DFID,

2001: Cited in Qadeem, 2005). The

situation of IDPs in Afganistan is more vulnerable. On top of the political

unrest, the regional drought too emerged as one of the dominating factors

affecting the socio-economic situation. This economic decline has exacerbated

the level o poverty and economic hardship throughout the country.

Serious human rights violations continued to occur and citizens were

precluded from changing their government or choosing their leaders peacefully.

In Taliban areas, the

Taliban’s religious police and the Ministry for the Promotion of Virtues and

Suppression of Vice (PVSV), enforced their extreme interpretation of Islamic

punishments, such as public execution for adultery or murder, and amputation of

one hand and one foot for theft. Furthermore, the Taliban government imposed a

strict version of sharia, Islamic law, on the country, prohibiting a wide range

of public activities. Many of these prohibitions were particularly designed to

restrict the freedom and rights of women. Tens of thousands of women effectively

remained prisoners in their homes, with no scope to seek the removal of these

restrictions. Women who violated these restrictions were punished severely and

their families held responsible for their behaviour. Displaced women who had no

shelter in which to maintain their privacy were doubly disadvantaged. Moreover,

women IDPs are facing sexual violations, such as abuse, rape etc.

In Afghanistan, IDP families,

whether settled in the city or camps, continue to feel insecure. They are facing

various problems, such as food shortage, human rights violations, no privacy,

malnutrition problem particularly among children, no schooling facilities, no

income generating activities, forceful return to their home etc.

IDPs come from different

backgrounds and experiences. The changes brought about by loss of status, death

of loved ones, loss of valuable property and life’s savings, in addition to

being displaced, result in immense adjustment difficulties. Children and women

are particularly vulnerable in such turbulent times as they are faced with

multiple burdens and have a lower social status. The majority of IDP families in

Afghanistan, having no potential breadwinner (i. e. with female or disabled head

of household), find life too hard to cope with. The widespread loss of assets

and sources of livelihood has required IDP families to find manual work to

obtain cash.

According to UN Guiding

Principles on Internal Displacement, the primary responsibility to provide

protection and humanitarian assistance to internally displaced persons within

their jurisdiction, however, Afghanistan government is yet to develop the

mechanism to support IDPs due to the political instability. Similarly, I/NGOs

could not reach to support IDPs in Afghanistan and women, children and

elderly/disabled people are more vulnerable. Therefore, UN Guiding Principles is

more applicable and relevant to provide support and care to IDPS in

Afghanistan.

Burma

(Myanmar)

For years, Internally Displaced

Persons (IDPs) in Myanmar have been subjected to horrific human rights abuses.

Yet their misery remains largely invisible to the outside world. Although the

international community has condemned the situation from afar, insufficient

action has been taken to protect those in need. IDPs in Myanmar are entitled to

a number of protections under international law; however the inadequate

realization of these protections calls into question the role and efficacy of

law in safeguarding human freedom and dignity. There are an estimated

600,000 to one million IDPs in Myanmar. Statistics are inexact because the

government tightly restrains outside monitoring. Like refugees, IDPs are

profoundly vulnerable in every aspect of their lives and legal entitlements are

particularly important to them. Their vulnerability is linked to a lack of

social, humanitarian and human rights protection and is often caused by conflict

and regime victimization. Nowhere is this more true than in Myanmar, where

a succession of cruel military regimes has had a stranglehold on the country

since the 1962 coup. Like its predecessors, the current military junta (called

the State Peace and Development Council [SPDC]) continues to perpetrate

large-scale human rights abuses.

Myanmar’s IDPs live in

sorrowful conditions. Those who are victims of forced relocation are placed

under the direct control of the military in relocation centres where they endure

untold exploitation as forced labourers, porters for the military and landmine

sweepers. Those who escape this fate usually become internal exiles, hiding in

the mountains or jungles with only what they can carry in a small bag; they are

constantly on the run. They exist in the shadows and silence, moving and cooking

only in the mist, constantly afraid that their children will alert the junta by

crying out from hunger. While an increasing number of people in the country face

a deteriorating humanitarian situation, Burma’s internally displaced are

particularly vulnerable and face acute humanitarian problems in health,

nutrition and education. In December, the UN Security Council received a

briefing on the human rights situation in Burma and the Association for South

East Asian Nations (ASEAN) openly showed concern for the first time by sending a

delegation to the country in March 2006. International and regional actors

should take every opportunity to raise the need for humanitarian access with the

military regime and should develop a common policy vis-à-vis the government in

order to improve protection and assistance to Burma’s internally displaced.

Displacement is limited largely to ethnic minorities, however ethnic Burmese are

not immune. The Karen, Karenni, Shan and Mon ethnic groups in eastern Myanmar

are most intensely affected. There are also chilling reports of displacement and

other abuses committed against minorities such as the Muslim Rohingya people

along the western borders with Bangladesh and India. Whether Buddhist, Animist,

Muslim or Christian, these people are deeply spiritual. Part of what makes the

military oppression so barbaric is that it shows utter disrespect for their

lifestyle and worldview. The junta’s extreme and disproportionate violence

forms an unconscionable contrast to the profound peace of most Burmese.

The domestic laws of Myanmar

provide grossly inadequate protection for the displaced and there is no

overarching regional protection structure in Asia. Hence, it is necessary to

look to international law for assistance. Under international law, protection

derives from a combination of human rights law, humanitarian law and, to a

limited extent, analogy with refugee law. The application of these bodies of

law, however, pre-supposes either ratification of relevant treaties or customary

international law. The international community should now use its full armoury

to secure greater protection for Myanmar’s internally displaced. It must

strike a careful balance between promoting national responsibility, condemning

abhorrent practices and intervening through negotiation or might.

India

Since the partition in 1947,

India had its own share of communal riots displacing millions of peoples. Yet,

India often dealt with such conflict induced displaced persons with ad hocism

and apathy. There is no standard on providing basic humanitarian standards —

adequate housing, food, health care, education and protection. It depends on the

whims of government of the day. Consequently, the programmes for humanitarian

assistance suffer from favouritism and discrimination.

At present, India has over half

a million conflict-induced Internally Displaced Persons respectively — 200,000

consisting of the Adivasis, Bodos, Muslims, Dimasas and Karbis in Assam;

2,62,000 Kashmiri Pandits from Jammu and Kashmir; 35,000 Brus/Reangs from

Mizoram and about 50,000 displaced persons in Tripura (http://www.tribuneindia.com/2006/20060101/edit.htm).

Children who are caught in

armed conflict situations in 14 out of 28 States are worse off. Hundreds of

children are subjected to arbitrary arrest, torture, rape, custodial death, and

extrajudicial executions every year at the hands of both the security forces and

the armed opposition groups (http://www.achrweb.org/press/2003/October2003/IND-CRC011003.htm).

Displaced people, without proper rehabilitation and resettlement often become

vulnerable to many hardships including HIV/AIDS. It is a generally known fact

that the increase in the CSW population, the number of rickshaw pullers, crimes

along the state and national highways, child labour are some of the direct and

indirect fallout of conflict-induced displacement in India (http://www.kanglaonline.com/index.php?template=headline&newsid=1359&typeid=0).

Women IDPs are subject to torture, economic hardship, sexual violence and lack

of privacy,

In this context, the Government

of India must develop a policy for providing humanitarian assistance and access

to essential food and potable water, basic shelter and housing, appropriate

clothing and essential medical services and sanitation to the conflict induced

internally displaced persons considering the provision and mechanisms provided

by UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement.

Nepal

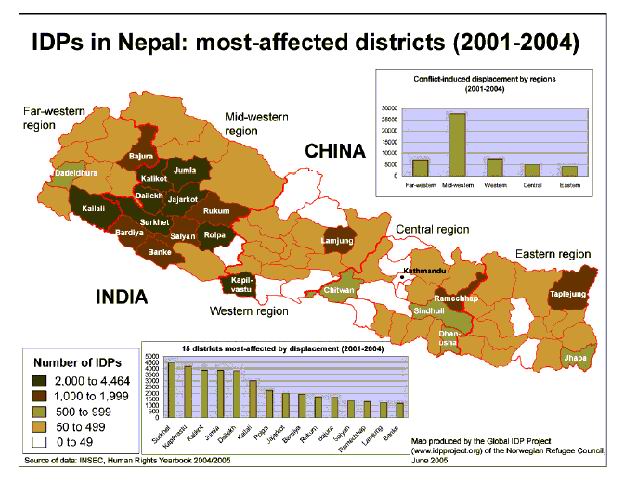

Conflict induced displacement

is a new phenomenon in Nepal which started in 1996 when the internal armed

conflict between Nepal Communist Party (Maoist) and the Government of Nepal

began. In Nepal, 12,865 people have lost their lives due to the conflict between

the Maoist and the government (INSEC, 2006). Reports from various organizations

over the last few years have quoted figures that could range from approximately

37,000 to 400,000 excluding those who may have crossed the border into India (SAFHR,

2005). The official estimate of the government is just 7000-8000. IDD Mission to

Nepal Reported that the best reliable estimate of Nepalese internally displaced

by the conflict should be up to 200,000 (cited in Aditya et. al, 2006).

Many

recorded incidents have revealed that many children are forced to associate with

armed forces and armed groups as militia, porters, kitchen helpers,

messengers/postmen and spies. According to CWIN, around 40,000 children have

been displaced in Nepal due to the armed conflict. During this period

(1996-2006) 419 innocent children have lost their lives, 454

have been physically injured, total of 29,244 children along with

teachers have been "abducted" while 230 children have been arrested by

the state security forces, 150 children are reputed to have been exploited in

the worst forms of child labour, and 224 children are facing health problems

after being displaced due to armed conflict (http://www.cwin.org.np/press_room/factsheet/fact_cic.htm).

The

UN expert on IDPs mentioned in his mission report that human rights problems and

violations faced by IDPs in Nepal are related to: poor security and protection;

discrimination; inadequate food, shelter, health care or access to education for

children; a lack of personal and property identification documents; and

gender-based violence, sexual abuse and increased domestic violence (www.un.org/News/Press/Docs/2005/hr4830.doc.htm).

The

youth are leaving their home due to threat of force recruitment in the militia.

Most of the youth are staying in the city centre. Some of them have fled to

India to seek employment and Gulf countries. According to report of Save the

Children Norway, about 10,000 young people crossed the border under the age of

14-18 during the July and August 2004 (Save the Children Norway, 2003).

New paradigm has been emerged

after Nepal’s latest political change (Jana Andolan II). Top level

negotiations between the government and the Maoists have been initiated.

However, the fate of the IDPs is yet to be decided. Both the rebel Maoist and

the government are not serious about the problems of IDPs. In this context the

relevancy of UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement is felt more acute

for the protection and care of IDPs in Nepal.

Pakistan

Army operations targeting

insurgent groups in Waziristan and Balochistan are the main causes of

conflict-induced displacement in Pakistan today. There is no official

information on the number of people displaced and access of journalists and aid

workers to the affected areas is tightly restricted. But best estimates from the

media and aid agencies are that at the very least many tens of thousands of

people have been forced to flee their homes in both areas, though most of these

will have returned home within a matter of weeks.

In Balochistan, the fighting

has been between tribal rebels and the army. Apart from longstanding demands for

increased political autonomy, development projects are fuelling the current

conflict in Balochistan as the local population demands increased control over

and more benefits from the exploitation of natural resources. The current unrest

started in 2003 and has intensified during 2005 and 2006, bringing 40,000 army

troops to the region to fight local militant groups. Estimates of the number

displaced at its peak are as high as 200,000.

In Waziristan, a government-led

operation started in March 2004 against militants connected to Taleban and al-Qaeda

hiding on the Pakistan side of the border. Since then, search operations and

fighting between rebel groups and the army have displaced an unknown number of

civilians. As many as 80,000 army troops are deployed along the border with

Afghanistan. The presidents of the two countries swap accusations of not doing

enough to prevent Taleban and al-Qaeda activities along the border.

Despite the large numbers displaced due to the conflicts, humanitarian aid from

outsiders has been rejected so far. As no one is allowed in to assess the

situation in the conflict-affected areas, it is not possible to verify the

little information that has trickled out about the displaced populations.

However, both national and international actors must insist that the

conflict-affected populations be granted basic assistance and protection during

displacement, as well as a safe and voluntary return to their homes when the

situation permits.

Sri Lanka

Conflict-induced

internal displacement in Sri Lanka has occurred on a massive scale. Official

estimates show that the number of IDPs peaked at over one million people in late

1995, nearly half of the north-east region's population. By early 2002, just

before the signing of the ceasefire, there were estimated to be some 683,286

IDPs, including 174,250 people at the 346 welfare centres around the island

(Gomez 2002). More recently, there is evidence to suggest that more than

four-fifths of the current population of the LTTE-controlled area has been

displaced (CPA 2003). However, it is clear that official figures do not cover

the sizeable population of former north-east residents who have not formally

registered as IDPs and now live in and around Colombo.

IDPs

in Sri Lanka can be classified according to a number of measures. Most

importantly, some IDPs have spent all or some of their displacement in camps or

welfare centres set up by the government or non-governmental organizations

(NGOs). Others chose not to enter these camps or centres, and fended for

themselves within the north-east, in the border areas surrounding the north-east

or in other parts of the island, particularly Colombo. Some IDPs are returnees

from other countries, usually from India (via transit camps set up to receive

them) or occasionally repatriated asylum seekers from the West.

In

a situation somewhat different from the bulk of Sri Lanka's IDPs, there are

approximately 100,000 Muslims who were evicted from homes in Jaffna and Mannar

by the LTTE in 1990. Most of this group settled in the districts in Puttalam,

Anuradhapura, and Kurunegala, and many remain there even after the ceasefire.

Their long-term residence and participation in local economic activities has led

to major changes in the local socio-economic context.

However,

this group has yet to achieve political inclusion in their new homes and the

resettlement of those amongst this group who are prepared to return will need

particularly sensitive handling.

There

are also various human rights violations of IDPs by both parties_ state and

nonstate. However, considering the

UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement the Common Humanitarian Action

Plan (CHAP) for Sri Lanka is a stand-alone humanitarian strategy document, time

framed by the end of 2006. As such, it is an agreement of humanitarian

stakeholders on the:

_

definition and analysis of the humanitarian context;

_

scenarios;

_

humanitarian consequences; and

_

priorities for humanitarian response.

4.

Conclusion

Above

discussion clearly shows that each and every country of South Asia is suffering

from conflict induced IDPs’ problem. In this region, IDPs’ livelihood

condition is vulnerable. There is a need to address the problems of IDPs and

make a separate mechanism and law to provide the protection and care to the IDPs.

For this, the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement is a milestone and

more applicable to conceptualize the IDPs’ concerns in the context of South

Asia.

5.

References Cited

Human

Rights without Frontiers Int. (HRWF), 2005, Internally

Displaced Persons in Nepal: The Forgotten Victims of the Conflict, Avenue

Wiston Churchill 11/33, 1180, Bruxelles

Chimni,

B. S., 2000, International

Refugee Law: A Reader, Sage Publications, New Delhi/Thousand

Oaks/London

Gomez,

Mario, 2002,

National Human Rights Commissions and Internally Displaced Persons Illustrated

by the Sri Lankan Experience,

Brookings Institution – SAIS Project On Internal Displacement

Centre

for Policy Alternatives, 2003,

Land and Property Rights of IDP

[i]

Norwegian Refugee Council, 2004

On

the basis of a close reading of Internal Displacement in South Asia write an

essay on how development have often led to displacement in South Asia.

Nanda Kishor

We

had tongues but could not speak, we had feet but could not walk, Now that we

have land, we have the strength to speak and walk.

The term “Development”

envisages a battery of changes, changes for the betterment of the community. It

involves the notion of progress, growth, upliftment and welfare of the

collective. This multifaceted term carries different meanings to different

people. For economists, it is an increase in the growth rate and per capita

income; for politicians, it is the acquisition of symbols of the modernization

and progress; for administrators, it is the achievement of the targets; and for

social anthropologists, it is the enhancement of the quality of life, standard

of living and satisfaction of basic needs.

‘Displacement

is a move which is effectively permanent, in the sense that the area where

people used to live has been transformed by the intervention, and there is no

going back’.

Involuntary

population displacements entailed by development programmes have reached a

magnitude and frequency that has been demanding a strong policy guided solution

in the present century. Involuntary displacement can be defined as displacement

of people (with coercion rather than cooperation) from a specific area and

reconstruction of their livelihood; sometimes can be called as rehabilitation.

There has been a record where 10,000,000 people each year are displaced

worldwide by infrastructural development programmes that may be dam

construction, urban development or transportation.

Historically social science has

been a discipline, which has taken a strong note in tune with recording the

effect. As Cernea puts it, “Public policy responses to hard development issues

can gain much from listening better to social research. But it is important to

state that social scientists themselves have to much more to equip governments

and public organizations with adequate practical and public advice”.

The present task of finding a long lasting sustainable solution to the problem

has shifted over to the arena of public policy. On the other side there has been

an inability of social science research to acknowledge the full impact of the

process of displacement. The

real challenge has come now, as this has to be grounded in a larger and

structural critique of development.

What constitutes adequate and

appropriate resettlement and rehabilitation of people displaced by development

projects has been a subject of considerable debate. “The involuntary

displacement destroys productive assets and disorganizes production systems, and

creates a high risk of chronic impoverishment that typically occurs along one or

several of the following dimensions: landlessness, joblessness, homelessness,

marginalization, food insecurity, morbidity and social disarticulation”.

The whole problem deserves the attention of the civilized population. The

violations of individual or group rights that have occurred due to the

development projects and resettlement have shattered the lives of thousands

running in number. Displacement is increasingly understood as a multidimensional

phenomenon, affecting not only the economic but also the social and cultural

sphere. Development projects cannot take the education, health facilities and

progressive feature for granted. Participatory

planning in displacement is severely restricted and what planning does take

place is effectively reduced to preparing for the actual relocation of the

people. Any preparation and planning for the long term needs of those who are

moved, tends to be delayed, or even abandoned, thus fields are not prepared

properly before move is clearly seen and which has successfully led to failures

of the resettlements.

There is also a large section

of the society that is of the view that the displaced can never be compensated

and taken care to the fullest. Having a strong and sustainable public policy can

contend this. There is also a view that the very concept of taking up a

development project which affects people can be used as an opportunity for

creating overall sustainable feature for the affected people. “It is

universally accepted that every human being has a right to just and sustainable

development and it can be taken as a strong base in development projects”.

Most of the time displacements leading to resettlements have failed to keep up

the “standard of living” of the people as they were there

previously. The renowned economist Amartya Sen defines “standard

of living” as “at a general level, the standard of living of an individual

can be seen to depend on his or her ‘entitlements’ to the commodities that

make the relevant activities possible”.

In wake of the definition we have not reached this position. The debate on

displacement can not be held in isolation. The problem has to be seen against

the background of our whole economy and in light of the needs of our country for

at least one generation. The essence of any displacement and resettlement must

be comprehensive enough to put them on a sustainable development basis rather

than just giving relief and a place to live.

The line of arguments presented

by different theoreticians and such other researches have most of the time

miserably failed in serving the purpose for what they have been instituted. It

is not that all the researches have gone waste and there are no positive

positions, there are instances where substantial achievement has been made by

different people, but it is to say that all the researches have not moved in the

same direction. The concept of failure here refers to that effort where the act

of convincing the people and politicians has not happened in respective

countries. The concern here is, that of making the people and the policy makers

to feel that development which leads to displacement and it is not addressed

properly is a negative development. Although there is a good amount work has

been done in this area, ironically most of the theories and empirical studies

have remained at the level of showing the problem and magnifying the problem but

at the convincing level and arriving at relative solutions. To put it in more

understandable and plain words, these works have not impressed the concerned to

the extent terrorism and communal violence. I consider both terrorism and

communal violence as essential violence which can never be tolerated but at the

same time even displacement having a veil of displacement which is not addressed

at proper level is also violence and it can be called as an organized and

government orchestrated violence. Just because it has happened from the side of

government that does not mean it can be taken for granted.

Historically, there has not

been a place where development has fared better and has reduced the agony of the

people. Involuntarily displaced people have shared more pains than gains caused

by so called development. The place of those displaced is given or used for

different purposes has not benefited the original dwellers of the place and what

is the logic and justice done for those whose place is snatched away but have

not benefited in any way? This type of inequitable distribution of benefits and

losses is not acceptable any way. It should not be accepted without any

resistance as inevitability, if so still there should be enough dialogue and the

participation of the local is very much required as to make justice to those

displaced. The concept has to be understood through the prism of social justice

which is very rarely invoked in the displacement and resettlement discourse. The

question is, is it equitable to support development programmes beneficial to

many people, if the same programmes undercut the livelihood of other groups and

have consequences which are life long and can not be overcome after a stipulated

time. This is the fundamental question we would like to pose to those who are

involved in the public policy process. Where ‘social justice’ is located in

the whole discourse? The concept of social justice had not been used very

frequently before 1995 when it was spelt out by the president of the world bank

of that time. The statement pronounced that ‘we must act, so that poverty will

be alleviated, our environment protected, social justice extended, human rights

strengthened. Social injustice can destroy economic and political advances’.

Practically speaking,

displacement has been a concept which has not spared any sphere of the world, to

be specific India. The scheduled tribes in India are the worst hit people with

regard to loosing the place of their livelihood in which they were living by

past few centuries. This is against the spirit of the constitution. The

constitution of India provides for special protection from exploitation and

social injustice, and promotion of educational and economic interests of the

weaker section, and in particular of the scheduled tribes and scheduled castes.

‘the reason why the tribal displaced may often be at risk, facing more acute,

longer lasting, impact of displacement than the non-tribal populations is

because of the cultural aspects of life. While the kinship of the general

population is spread far and wide, this is not true of the tribal groups whose

habitation may be confined only to a certain specific areas. Any unsettlement

may become a more crushing blow to their cultural life than in case of the

former. Second reason is that of

education and the third being that the tribal people depend for their living

including trade, profession and calling , on roots and fruits, minor forest

produce and forest material than the general population”.

The

experience of the past almost five decades of planned development demonstrates

that large-scale displacement is inbuilt in the patterns of economic development

which themselves are incompatible with social justice and genuine long-term

environmental sustainability. The social impacts of the recent thrust, towards a

greater market driven economic process, point to realities that as the national

and global economies penetrate deeper into every part of the country. The lives,

livelihoods and lifestyles of those who critically depend on the natural

resources base will continue to be seriously threatened.

‘Displacement

is an unequal struggle for the control of the natural resources and the powerful

minority will continue to appropriate most of them to their own benefit. This

process of the further impoverishment of the marginalized sections and transfer

of their resources will continue, unless the weak organize themselves to resist

this onslaught’.

While

the families getting displaced make a sacrifice for the sake of the community

and the country at large, the planners seem to view their uprooting and

resettlement as one of the unavoidable logistical operations of project

building. Therefore, the problem of resettlement has not gone beyond

compensation (kind or cash). There is little understanding of the ethos of the

people who are getting displaced. The logical steps in the process of

displacement and rehabilitation must be elaborated as time bound conditions,

e.g. the kind of base line survey, which uses a participatory approach, the

criteria of compensation, and the requirements of total rehabilitation.

Land

Acquisition laws:

The law enabling displacement

in this country is basically faulty as still the land acquisition act 1894 is

invoked after a small amendment in the year 1984. There

are but instances of a statutory order which is so constructed as to legitimate,

and facilitate, the displacement of persons, as of communities. In its ordering

of priorities, it has not reckoned with displacement. Instead, it has attributed

a cost to the acquisition process, and displacement is an unstated incident in

the process. Law depends, for its legitimacy, on its popular acceptance. The

patent injustice that have resulted from employing the extant statutory regimes

for situations which it could never have been intended-and mass displacement is

an outstanding example and the popular condemnation

that has followed, have concerned the law into rethinking its

propositions. To get the laws to revise its priorities, to relocate expediency,

to redefine development, to reassess the meaning of cost requires a liberal dose

of legal imagination, political will and the induction of empirical knowledge.

The concept of public purpose

is of high controversy, it all started with the British. But the real situation

started during the period of Nehru being the Prime Minister of India and went

ahead with having large public sector projects which involved displacement of

lacks and thousands of people. The concept involved was ‘larger public

good’. But the very concept is problematic as the ‘larger public good’ is

of whom? The field has to be defined to whom it applies and what purpose. A

project helping ten lack people cannot displace more than ten lack people. The

number is tentative. It is understood that the larger projects bring prosperity

to the nation but the prosperity not at the cost of our own people. It is sure

that the person who sacrifices many a times does not get the benefit for his

sacrifice; the case stands as an irony. Before the land acquisition itself a

proper compensation has to be made and make sure that the person affected is

restored his income and the life he was living before. Until and unless this

criteria is fulfilled every act and statute is a failure and of no use. “Paradigm

of development that has found favour with the planners makes displacement of

large number of people, even whole communities, and an unavoidable event. The

utilitarian principle of maximum happiness for the maximum numbers has been

invoked to end respectability to making the lives of communities into a cost in

the public interest. The law is ill equipped to counter this attitude and in

fact abets it by lending the force of state power”.

The law has become so ridiculous that sometime it is worse than the orders of

the state of affairs in Bihar. For example land acquisition act that of railways

acts of 1989, which is very apt for the present situation. The extent of powers

is vivid in the clause says that in a very crude way ‘do all…. acts

necessary for making, maintaining, altering or repairing and using the

railway’. Interestingly the land belongs to the government directly and here

too the displacement takes place and the involuntary resettlement has become

inevitable.

It is, at this juncture, it is

very appropriate to have a look at the legal system again and come in terms to

have a better fed law which can protect the displaced. “whatever be the shape

of laws to come, we may conclude that a separate legal regime in India is

necessary not simply for compiling the existing provisions but also for plugging

their loopholes”.

Direct

displacement in the form of evictions to more indirect processes that force

people to move as a result of indirect chains of causation, as are mediated by

the market and ecosystems, for example, the picture becomes still more

complicated. What does it mean to be forced to move? The libertarian

position, that only violations of one’s rights as a person and informal

dweller in the form of the deprivation of freedom of movement (other than by the

constraints of the property rights of others), of freedom of expression, and of

possessions, does not capture the complexity of loss of freedom resulting from

more indirect effects and, more widely, from structural social processes. While

treating only directly forced displacement as manifestations of coercion is

clearly insufficient, interpreting all movements of people as coerced and thus

as forms of displacement would just as clearly be going too far in the other

direction. It would deny that mobility, the freedom and capacity to move, is

desirable. Mobility represents choice. Those without it are deprived in an

important way. This brings out another important distinction to make, namely

between those who stay because they choose to do so and those who stay

because they cannot move. The challenge is to articulate what forms of

movements are objectionable and on what grounds they are objectionable,

and in the process to distinguish between desirable and objectionable forms of

staying.

Being

Gender sensitive:

The

life of women is often worsened by displacement and resettlement. ‘It is true

that there have been cases where they have benefited, but such cases are

exceptional’.

The exclusion of gender considerations in the planning and implementation of

displacement and resettlement is seen in the study. Largely, technical issues

have been given more importance than socio-cultural and socio-economic

considerations. Equity has not been an explicit goal of development projects. It

has been fallaciously assumed that all benefits are shared equally by a

community or society, without analyzing the relational aspects of large dams or

other infrastructure projects and how these are linked with issues concerning a

wider political economy. The concept of displacement as Sangeeta Goyal

says can’t be taken for granted. The people with absolutists stand have to

keep in mind that the fight by the civil liberty groups for the absolute and

proper resettlement is to make the concerned government to feel responsible and

avoid it by taking decisions in haste. The efforts should be made by the

concerned agency to make the resettlement the best then at least it will end up

in being good. If at all the

process starts with the notion that there can never be an absolute resettlement

as that of the position before displacement then the whole process will end up

in being not up to the mark of even being manageable. There is a greater need

for more gender-aware and gender-sensitive policies concerning the planning,

implementation and monitoring of resettlements. These policies should be

extended to include all the displacement affected areas.

Developmental

processes that infringe upon the human rights of any section of society are

inimical to the long-term goals of progress. Development activities cannot be

taken up with the use of coercion and force. It is important to set up human

rights monitoring institutions and ensure the protection of the human rights of

the affected population. As women are generally more vulnerable to manipulation

by the state and other agencies, special care should be taken to ensure that

women are not subjected to any kind of violence as a result of displacement due

to development projects. “Displacement from Livelihood has the potential of

developing into a fully blown crisis of internal displacement in future”.

If at all we are able to avoid this major problem then there are all the chances

of avoiding displacement in future.

Concept

of Local Consensus:

The

concept is of high utility in the displacement, resettlement and rehabilitation

process. Most of the time it happens that the political leaders and the local

representators try to avoid the problem of the oustees and they never seem to be

bothering about the problem of the oustees. In a genuine case in Bengal, the

land acquisition which happened was for the new Industrial town of Haldia,

across the river from, and to the south of Calcutta. The most genuine part of

the resettlement and rehabilitation was that there was a ground level agreement

between political representatives. This represented the local consensus

as the ruling and the opposition party came together to the help of the people.

These types of agreements would enable the administration to carry out the

decision smoothly.

Where

population displacement is unavoidable, a detailed resettlement plan with

time-bound actions specified and a budget are required. Resettlement plans

should be built around a development strategy; and compensation, resettlement,