This report is a product of notes and writings and prepared by the participants, faculty members and members of CRG desk for the winter course on forced migration. Thanks are to the participants and all others who contributed to it. Thanks are in particular to the UNHCR, the Brookings Institution and the Government of Finland whose generous help and advice made the programme possible.

Contents

- A Unique Programme

- Structure of the Course

- The Participants

- Members of Faculty and Speakers in Roundtables

- Partnerships: Supporting and Collaborating Institutions

- Schedule of the 15-day Programme

- Distance Education, the Modules and Assignments

- Creative Assignments

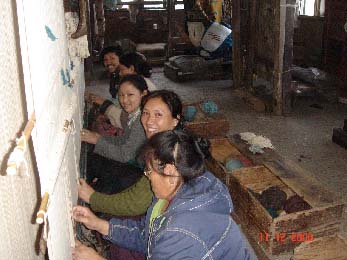

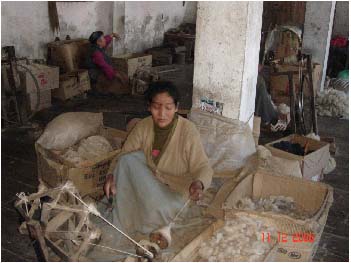

- Field Visit

- Public Lectures

- Interactive Sessions

- The Film-Tales of the Nightfairies

- Inaugural and Valedictory Session

- Evalution

- Follow-Up Activiries

- CRG team on Forced Migration

In the current political, social, and cultural climate of India, South Asia, and the world in general, the significance of a human rights and peace education programme on the inter-linked phenomena of massive forced migration, racism, and xenophobia cannot be overestimated. Attacks on civilians, atrocities on individuals and groups mostly belonging to minority communities, public espousal of national chauvinism, sexism, and masochism, intolerance, majoritarianism, and wars and war hysteria have increased. The scenario is marked by less tolerance, increase of hatred against foreigners, immigrants and refugees, a reduction of the civic-cultural space for discussion, debate, and dialogue in a context dominated by globalisation and a concomitant reduction of capacity of the states to listen to public voice for democracy, tolerance, and inter-cultural understanding. The situation is compounded by two trends: on one hand, education is becoming more nationalistic, majority-centric, consumerist, and is littered with hate-words and hate-speech, which impact on mass culture and reinforce the mass populist basis of war and militarism; on the other hand, there is a general decline of human rights standards, erasure of human rights protection mechanisms, and an increasing contempt and derision for appeals to heed to human rights laws and humanitarian laws in public life and follow the ethics of considerations for vulnerable sections of society.

Ranabir Samaddar, Director of Calcutta Research Group addresses course participants

Never before in this region

was there such dire need to work for peace education that would be based on the

ethos of culture of peace so as to foster respect for human rights.

Most conspicuous, because of

conflicts, developmental policies, and environmental hazards, population

displacement has taken alarming proportions and the victims of forced

displacement are becoming targets of xenophobic frenzy, inter-state rivalry,

suspicion, and hate speech and hate acts. The flows are of mixed and massive

types called for grater atten5tion to human rights standards and humanitarian

protection – across boundaries and within nation-states. In short, the

situation calls for greater mobilisation of the civic-political space, of human

rights, peace, and humanitarian institutions and activists, grater dialogue

among all concerned on the related issues of rights, justice, and protection.

Developed through last few years as a programme on human rights and peace education, the

annual winter course on forced migration organised each year by the Mahanirban

Calcutta Research Group (CRG) has come to be recognised in the region of South

Asia as one of the most well known educational programmes on issues of rights

and justice relating to the victims of forced migration. In the from of a

certificate course, certified by the UNHCR and supported by the Government of

Finland and the Brookings Institution, the winter course is aimed at scholars

and educationists working on issues of rights and justice, functionaries of

humanitarian organisations, national human rights institutions, peace studies

scholars and activists, and minority groups, refugee communities, and women’s

rights activists. Participants come from all over South Asia, with some joining

from Thailand and Burma, and from the Europe and the Americas. The course

attracts a renowned international faculty, and is now recognised by the National

Human Rights Commission in India, and several universities along with various

grassroots organisations have collaborated over the years to make it a success.

There

are several features of the course, which make it a unique programme.

Readers of the report will find the details in subsequent pages; however it

is important to summarise them and place them at the beginning:

(a) Emphasis on distance education, its innovation, and continuous

improvement through interactive methods, including the use of web-based

education;

(b) International standard, rigorous nature of the course, field work,

and a comprehensive regional nature of the course;

(c) Emphasis on experiences of the victims of forced displacement in the

conflict zones; such as the Northeast, Jammu Kashmir, and Jharkhand.

(d) Emphasis on gender justice

(e) Special attention on policy implications

(f) Follow up programmes such as spreading it to universities, innovating

local modules, training participants to become trainers of the future

programmes;

(g) And, finally building up

the programme as a facilitator of a network of several universities,

grassroots organisations, Mothers Fronts, research foundations, UN

institutions etc.

The Fourth Annual CRG Winter Course on Forced Migration concluded on 15 December 2006. Although this course is called a course on forced migration it also discusses the root causes for migrations/displacements, and so issues such as racism, immigration and xenophobia in the context of displacements fall within its purview and are discussed in some details. The major thrust area of this course is South Asia although examples from other regions are also brought in for purposes of comparison and analysis. The course, as has already been mentioned earlier, is an outcome of the ongoing and past work by the CRG, and other collaborating groups, institutions, scholars, and human rights and humanitarian activists in the field of refugee studies and on displacement and human rights. The course structure is intended to take cognisance of the gendered nature of forced displacement in South Asia. It pays special attention to victim’s voices and their responses to national and international policies on rehabilitation and care. The course builds on CRGs ongoing research on forced displacements in the region and hence it is constantly evolving. It analyses mechanisms, both formal and informal, for empowerment of the displaced. It pays particular attention to different forms of vulnerabilities in displacement without creating hierarchies. It is built around six modules, four of which are compulsory and two others optional. From the two optional modules the participants are expected to select one for their study.

The compulsory

modules:

1. Nationalism, ethnicity, racism and xenophobia

2. Gendered nature of forced migration, victim-hood, and gender-justice

3. International, regional, and national regimes of protection

4. Internal displacement – causes, linkages, and responses

The optional

modules:

5. Resource politics, environmental degradation, and forced migration

6. Ethics of care and justice

This year the course activities besides the writing assignments, included workshop assignments, group discussions, field visit, creative sessions, review discussions, and face-to-face sessions with resource persons experienced in related areas and with refugee activists working with refugees living in camps. The course also included film and documentary sessions.

Duration and

activities

The course was of three (3) months duration with two and half months duration of distance education, communication on related issues of displacement studies, course assignments by participants followed by fifteen days of direct course work in a winter workshop. Upon the participants being selected, course material was sent to them in a phased manner Short introductory note on each module was sent to the participants; along with these notes, lists, bibliographies, and other announcements were also sent. The reading material was also sent to the participants in a phased manner. For review assignments and term papers lead-questions and discussion points were sent at regular intervals. Each module had a tutor and a number of faculty members. On the basis of the modules chosen by them the participants were encouraged to contact the faculty persons for necessary advice and inputs. Chat sessions were organised so that participants could discuss their assignments with module tutors.

Participants

were required to prepare an assignment paper each and bring the papers with them

for the workshop where the papers were discussed. These papers were first read

and commented upon by the module tutors and then made available for wider

circulation and discussion on the CRG website. The participants were also given

assignments termed as creative assignment so that the period of three months

could also be used for training in communication aspects of humanitarian and

human rights work, and other practical aspects such as providing the

participants with information and documentation skills, preparing local data

base, campaign for fund-raising for human rights and humanitarian efforts, and

report writing. Creative assignments were made mandatory this year and its

results were varied and rich. Participation in the field visit was also

compulsory.

The

preparation of course material was of great significance. The course material

included mandatory, optional and supplementary material. The mandatory material

included a number of books, essays and web-based material. Supplementary

materials including a short write-up on fieldwork was handed

to them when they arrived in Kolkata. Three weeks before the participants arrived

in Kolkata they were given workshop themes. They were required to participate in

one of the workshops. Participants were graded on all these assignments and on

the valedictory day these grades were handed to them. Since 2005 the course also

includes two optional modules. The participants were

asked to select any one of the modules of their choice. They were given one assignment from the optional

module that they selected. They had to write a review essay analysing some of

the reading material given in that module.

Participants

Twenty-four participants were selected for the course, of whom twenty-one could complete the course. These participants were selected through public notifications and were drawn from backgrounds of law, social and humanitarian work, human rights work, and academic and research work. Most of them came from South Asia but few were also from other regions such as Europe, Africa and Australia and brought forth with them wider experiences of refugee-hood and of rehabilitation and care. Those who could not complete the course were to do so mainly due to visa problems.

Faculty

The faculty was drawn from people with recognised backgrounds in refugee studies, studies on internal displacement, university teaching and research, humanitarian work in NGOs, legal studies, UN functionaries, particularly UNHCR and ICRC functionaries; public policy analysis, journalism, and concerned human rights activism and humanitarian work. Attention was paid to diversity of background and region. Importance was attached to the requirements of the syllabus; the faculty was also involved in developing on a permanent scale a syllabus, a set of reading material, evaluation, and follow-up activities. The resource persons also helped in harmonising the syllabus of this course with the requirements of the participants, and similar syllabi in various universities, workshops, and courses. They graded participants on their skills such as speaking and writing skills, analysis of themes chosen, execution of creative assignments etc.

Evaluation

The participants were evaluated by a number of

resource persons. The core faculty

evaluated each of their assignments. All the resource persons present evaluated their presentations,

including the presentation of their term paper. They were given a grade for the distance education segment and

another for the Kolkata workshop. At the end of the course they were given a cumulative grade. The course is

equivalent to six credit hours of graduate level work.

The course has a built in evaluation system. Each participant is required to

present a written evaluation and each resource person is also expected to do

the same. Every year CRG invites

independent scholars of renown, social activists and administrators to evaluate

the course. This year Professor Tarja

Väyrynen of Tampere University, Finland, Professor Barbara Ramusack of

University of Cincinnati, USA, and Dr. Khalid Koser of the Brookings-Berne

Project on Internal Displacement evaluated their course. Excerpts from their evaluation are presented

in Section 14.

Follow-Up

Considering

the growing popularity of the course the advisory committee asked the CRG

organisers to look into possibilities of organizing short courses in

collaboration with willing centres and departments of Universities in India as

follow-up activity. On the basis of such advice the CRG is now in the process

of designing a number of short courses for different Universities and research

centres. This year two such short courses were held. The first was held in

Guwahati and it was organised in collaboration with Panos, South Asia. The

second course was held in Delhi in collaboration with Jamia Milia Islamia

University (JMU).

Apart from this a number of workshops on forced migration were held in different

parts of South Asia. The CRG also collaborated with a number of institutions and

organised a number of public lectures. This year three fellowships were given to

the participants of the Winter Course. Also CRG conducted a many research

projects on the theme of forced migration. For a detailed report on follow-up

activities please read Section 15.

The follow-up activities of the winter course have now assumed the character of

an entire programme with other allied work. The CRG established the forced

migration desk to look after the entire programme.

Abdur Rashid

is a Senior Programme Officer at the Refugee and Migratory Movements Research

Unit (RMMRU) in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Dilip Gogoi

is a lecturer in Political Science at Cotton College, Guwahati, India.

Eeva Puumala

is a doctoral student and research assistant at the Tampere Peace Research

Institute (TAPRI), Finland.

Hina Shahid

is a Program Officer with Action Aid, Pakistan.

Jason Miller

is a researcher monitoring human rights in Burma.

Judith Macchi

is pursuing her Master’s degree in Human Geography at the University of Berne

and working on her Master’s thesis on the Sri Lankan immigrants to

Switzerland.

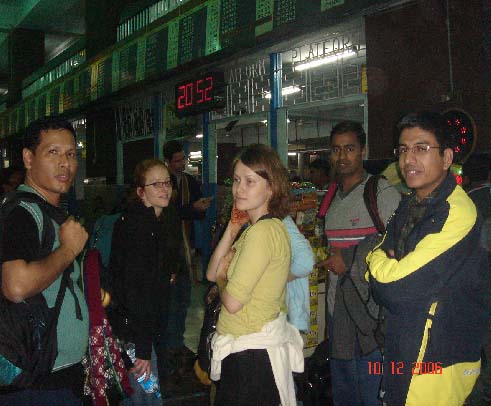

Ksenia Glebova,Eeva Puumala, Uma Joshi & Judith Macchi

Khaleel Ahmed is an Assistant Registrar (Law) with the National Human Rights Commission of India.

Ksenia Glebova is a freelance journalist from Finland specialising in refugee and displacement issues.

Madhumita Sengupta is lecturer in History at Rani Birla College, Kolkata, India.

Malkit Singh is a doctoral student in Political Science at the Punjab University working on issues of state, militancy and human rights in Punjab, India

Mostafa Mahmud Naser is a lecturer in Law in the Department of Law, University of Chittagong, Bangladesh.

Nanda Kishor is a doctoral student at the Department of political science, University of Hyderabad are working on the subject of urban displacement and sustainable urban development.

Nir Prasad Dahal is a researcher working for the Nepal Institute for Peace, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Oluwatoyin Oluwaniyi is a lecturer in Political Science at the Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria.

Om Prakash Vyas works for the Investigation Division of the National Human Rights Commission of India.

Course participants from India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan

S.Y.Surendra Kumar is a doctoral student at the Jawarharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and a lecturer in Political Science in Bangalore University, India.

Saba Hussain is working for Greenpeace, India.

Shiva Kumar Dhungana is a Research Officer working for a Kathmandu-based NGO Friends For Peace, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Uma Joshi works for the National Human Rights Commission of Nepal.

Vanita Banjan is a senior lecturer in Political Science at the SIES College of Arts, Science and Commerce in Mumbai, India.

Ajay Gandhi Human rights activist and researcher, McGill University

Flavia Agnes Women’s Rights Activist, Majlis, Mumbai

Hameeda Hossain Ain O Shalish Kendra, Dhaka

Hans-Joachim Heintze Professor, University of Ruhr, Bochum, International Regime of Refugee Protection

Jagat Acharya Bhutanese Refugee and Activist, Nepal Institute of Peace, Kathmandu

K. M. Parivelan Information Officer UNDP/TNTRC Chennai

Faculty members in discussion before the inaugural session

Keya Dasgupta

Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata

Khalid Koser Deputy Director, Brookings-Bern Project on

Internal Displacement, Brookings Institution

Manabi Majumdar

Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata

Manuela Bojadzijev

Projekt Migration, Frankfurt and Berlin

(European Experiences of Racism and Immigration)

Mario Gomez

Berghof Foundation, Colombo (Human Rights Commission and the Protection of the

IDPs in Sri Lanka

Meghna Guhathakurta Professor, Department of International Relations,

University of Dhaka, Bangladesh

O.P. Mishra

Centre for Refugee Studies, Jadavpur University

Oishik Sircar

Pune ILC, The Politics of Asylum Jurisprudence and

International Protection

Paula Banerjee Historian and women’s rights activist, member of the Calcutta

Research Group, Faculty, Department of South and South-East Asian studies,

University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India.

Pradip Phanjoubam

Editor, Imphal

Free Press

Ranabir Samaddar Political thinker and Director, Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata,

India.

Sabyasachi Basu Ray

Chaudhury Secretary of the Calcutta Research Group and

Faculty, Department of Political Science, Rabindra Bharati University,

Kolkata, India.

Samir K. Das Political analyst on the North East and member of the Calcutta

Research Group, and Faculty, Department of Political Science, University

of Calcutta, Kolkata, India.

Sohini Ghosh Filmmaker,

Jamia Milia Islamia University

Subhas Ranjan

Chakraborty President of the Calcutta Research Group and

Faculty Presidency College.

Sudeep Basu Institute of

Development Studies, Kolkata

Sumbul Rizvi UNHCR, New Delhi

The

Government of Finland, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, New

Delhi, and the Brookings Institution, Washington DC are the sponsors of the

programme. With their un-stinted support and goodwill, the programme has become

one of the most well known events in the field of studies on forced migration

studies, and an academic event in Kolkata.

Preparation for the Fourth Winter Course on

Forced Migration commenced on 14 December 2005, a day before the Third

Winter Course formally ended. By

that time CRG members and its collaborators had realised that the Winter

Course has grown into a full-fledged programme with components of

research, networking, particularly partnership between Indian and Finnish

institutions, and training under innovative and different formats.

This was later accepted and endorsed by the advisors during the

advisory committee meeting in June 2006.

The collaborative nature of the programme was underlined from the

beginning by the participatory nature of the advisory meeting. The

Advisory Committee Meeting of the Fourth CRG Winter Course on Forced

Migration was held in Swabhumi Kolkata, on 13 June 2006. The participants

included the following:

Abu Ahmed (OKD)

Ajay Darshan Behra (Jamia

Milia Islamia University)

Anita Sengupta (MAKAIAS)

Anna-Kaisa Heikkinen

(Government of Finland)

Jyrki Käkönen

(University of Tampere)

Krishna Banerjee (Khoj

Akhon, CRG)

Monirul Hussain (Guwahati

University)

Oishik Sircar (Pune

University)

Paula Banerjee (CRG)

Pradip Kumar Bose (CRG)

Pritima Sharma (CRG)

Ranabir Samaddar (CRG)

Ritu Menon (Women

Unlimited)

Sabyasachi Basu Roy

Chaudhury (CRG)

Samir Das (CRG)

Sharmistha Chakraborty

(Calcutta University)

Shivaji Pratim Basu

(Sri Chaitanya College)

Shoumitra Dastidar

(Independent Filmmaker)

Shreyashi Chaudhuri (CRG)

Subhas Chakraborty (CRG)

Sudeep Basu (IDSK)

Sudhir Chowdhury (NHRC)

Sumbul Rizvi Khan (UNHCR)

Swati Ghosh (Rabindra

Bharati University)

Uttara Chakraborty

(Bethune College)

Several suggestions

emerged as a result of the advisory meeting including greater engagement

with the concept of ‘refugee’, more emphasis on Bhutanese and Nepalese

refugees in the course, and introducing the Sub-Saharan as well as Latin

American dimensions would make the course more interesting and

far-reaching.

It was also acknowledged that collaboration with Finland is proving

significant as more Finnish students are getting interested in joining the

course. Sending selected Winter Course participants to Tampere University

for a week-long exposure trip was one of the suggestions later put into

practice.

Four areas of experiment were identified

including structuring of module, distance education, participants profile

and participants assignments. Suggestions were made for a short-term

course with SDPI or LUMPS in Islamabad and ICES in Colombo, including

growing violence against the displaced as an optional module, looking at

the refugee problem as a cultural problem and making the field visit

longer in duration. Also, the distance education segment can be reduced so

that the time for direct orientation workshop in Kolkata can be increased.

In the assignment component CRG can also think of a collaborative research

of participants of two or three countries together.

Sumbul Rizvi, UNHCR Protection Officer

In terms of

furthering existing co-operation and creating new collaboration networks,

Professor Jyrki Käkönen confirmed his intention to further CRG-Tampere

University exchanges. He

stated that Dr. Paula Banerjee was to be invited to teach a course in

Tampere for one week. This

course can be on forced migration. Professor Ranabir Samaddar has been

invited by Turku University as part of the emerging cooperation. Professor

Abu Ahmed stated that the OKD Centre was willing to sign a MOU with CRG

for further exchanges.

Support for the winter

course has also been expressed at individual level. Several faculty

members came without full or any travel support and offered to contribute

their knowledge and expertise for the benefit of the course. Many

institutions such as the National Human Rights Commission have supported

the course by sending participants. Finally, the cooperation from various

quarters in circulating the announcement on the course was tremendous. In

all these, the cooperation of the participants and the ex-participants was

the most valuable asset. CRG remains indebted to all for making the course

a success.

Due to the growing popularity of the course the advisory committee asked

the organisers to look into possibilities of organizing short courses in

collaboration with willing centres and departments of Universities in

India as follow-up activities. As a result of a series of follow-up

activities the CRG is building partnerships with many new institutions. A

number of organisations and institutions have shown willingness to

collaborate with CRG on this. Included in these are NALSAR,

Secunderabad, Jamia Milia Islamia University, New Delhi, Omeo Kumar Das

Centre, Guwahati, Punjab University, Chandigarh. Women’s Studies Centre,

Utkal University, Department of Law, Guwahati University, Department of

Political Science, Rabindra Bharati University, Department of South and

South East Asian Studies, Calcutta University and several Finnish

institutions. Besides as reported earlier the CRG has collaborated with a

number of institutions to organise public lectures and discussions as part

of its follow-up activity. CRG remains grateful to all the organisations

that have showed willingness to collaborate on programmes on forced

migration.

Short Course in Jamia Milia Islamia

A

five-day course on issues of forced migration was held in Jamia Milia

Islamia (JMI) University with full cooperation of the Honorable Vice

Chancellor, Professor Mushirul Hasan.

The course coordinators were Ajay Darshan Behera of JMI and Paula

Banerjee of CRG. Lectures were delivered by Rashmi Doraiswamy (JMI),

Navneeta Chaddha Behera (Delhi

University), Ritu Menon (Women Unlimited), Urvashi Bhutalia (Zubaan), and

Walter Fernandez (NESRC) among others.

Details of the above course are provided later.

Fellowship

Program

This year three fellowships were given to the participants of the Winter

Course. Eeva Puumala came

from Tampere University and spent a month in CRG in December 2006 working

on the theme, Calcutta: A migrants’ City. Two Indian participants, Nanda

Kishore and Priyanca Mathur Velath were sent to Tampere for a week and

they worked on Finland’s policies of providing asylum in February 2007.

Again details can be found on the following paper.

Khalid Koser of the Brookings Institution in an interactive session with the participants

Workshops Held

Prior to the Winter Course a number of

workshops were held. One workshop was held in collaboration with the

Punjab University, Chandigarh. In

that seminar CRG organized two panels on the issue of forced migration.

The speakers in these panels included Samir K. Das, Sabyasachi Basu

Ray Chowdhury, Paula Banerjee and Mika Aaltola.

In April 2006 CRG organized a workshop in Guwahati in collaboration

with Panos, South Asia. The participants were from different parts of East

and Northeast India. Other than CRG members the resource persons included

scholars and activists from Northeast India such as Walter Fernandez,

Sujata Dutta-Hazarika, Sanjay Borbora etc. In the summer of 2006 CRG

members Ranabir samaddar, Sanjay Chaturvedi and Anita Sengupta

participated in a seminar on the issue of borders in Europe and Asia.

In August another workshop was held in Kohima, Nagaland in

collaboration with Naga People’s Movement on Human Rights.

Between January and

March 2007 a number of workshops were held in different parts of South

Asia on the occasion of the release of the report on “Voices of IDPs”.

The report has been released in Katmandu in Nepal in collaboration with

Nepal Institute of Peace in February 2007.

Around the same time the report was released in Guwahati.

Panos, South Asia facilitated the release in Guwahati.

This was followed by a daylong trip of the media people to camps in

Kokrajhar, where part of the fieldwork was held. Detailed report on this

is in the later part of this report.

Public

Lectures

The CRG collaborated

with a number of institutions to organize public lectures before and after

the course. With the

Institute of International Law Jeevan Thiagrajajah’”s lecture was

organized in New Delhi. Ranabir

Samaddar and Paula Banerjee delivered two public lectures in Dhaka

University, Bangladesh in August 2006.

CRG members including Sabyasachi Basu Raychowdhury delivered public

lectures in February 2007 in Katmandu in collaboration with Friends for

Peace in Nepal. In Kolkata

Professor Sonia Dayan-Hezbrun of University of Paris VII, France addressed

a public lecture in February 2007.

Research

Programme

The CRG has designed

and organized a number of researches on the theme of forced migration in

collaboration with different institutes in South Asia.

The research on the “Voices of IDPs” was organized in

collaboration with a number of human rights group.

In Sri Lanka the research was conducted in collaboration with

National Peace Council in Colombo, in Nepal with the Nepal Institute of

Peace, Katmandu and in Bangladesh with Research Initiative of Bangladesh,

Dhaka.

The CRG has been able to set-up a well-organized network of institution

and individuals passionately committed to the cause of forced migrants in

South Asia. In the field of studies and discourses on forced migration it

has been able to establish itself as a premier institution.

Fourth Annual Winter Course on Forced Migration (1-15 December 2006, Kolkata)

(Venue – Conference Room, Swabhumi, Kolkata, unless otherwise stated)

Course Modules

(Compulsory)

A. Forced migration, racism, immigration and xenophobia

B. Gender dimensions of forced migration, vulnerabilities, and justice

C. International, regional, and the national legal regimes of protection, sovereignty and the principle of responsibility

D. Internal displacement with special reference to causes, linkages, and responses

(Optional)

E. Resource politics, environmental degradation, violence and displacement

F. Ethics of care and justice

Plus Field Visit, Seminars, Course Assignments, Workshops, Public Lectures, etc

1 December (Friday)

5.00 PM Inauguration, Sojourn Hotel (Salt Lake, Sector III, near Salt Lake Stadium, Kolkata 700106)

Inaugural Lecture Flavia Agnes, Women’s Rights Activist, Majlis, Mumbai

2 December (Saturday)

9.30 – 11.00 AM Explaining the Course and foundational concepts / Ranabir Samaddar

11.00 – 11.30 AM Tea break

11.30 – 1.00 PM Module B / Sumbul Rizvi, Protection Officer, UNHCR, India (Statelessness and Women)

1.00 – 2.00 PM Lunch break

(Flavia Agnes, Manabi Majumdar, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata; Ruchira Goswami, National University of Juridical Sciences, Kolkata,Priyanca Mathur, (participant) Moderator: Paula Banerjee, CRG & Calcutta University, Kolkata)

3.30 – 4.00 PM Tea break

4.00 – 5.30 PM Module A / Ranabir Samaddar

6.00 – 8.00 PM Library hours

3 December (Sunday)

9.30 – 11.00 AM Module A/ Manuela Bojadzijev, Projekt Migration, Frankfurt and Berlin (European Experiences of Racism and Immigration)

11.00 – 11.30 AM Tea break

11.30 – 1.00 PM Participants’ presentation under Module A (Moderator: Ranabir Samaddar)

1.00 – 2.00 PM Lunch break

2.00 – 3.30 PM Module A/Jagat Acharya, Bhutanese Refugee and Activist, Nepal Institute of Peace, Kathmandu ("Political, Social and Economic Discriminations in Bhutan and Bhutanese Refugee Question")

3.30

– 5.00 PM Panel

discussion on "Do Partition Refugees have a Right to Return? (

Jagat Acharya, Ranabir Samaddar, Subhoranjan Das Gupta,

Institute of Development

Studies, Kolkata, Samir Das, CRG & Calcutta University, Kolkata/ Vanita Banjan, Malkit

Singh,(participants) Moderator: Keya Dasgupta, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences,

Kolkata)

6.00 –

8.00

PM Library hours

4 December (Monday)

9.30 – 11.00 AM Module B/ Paula Banerjee, (Gender dimensions of Forced Migration)11.00 – 11.30 AM Tea break

11.30 –

1.00 PM Module

B/ Manuela Bojadzijev, (EU and European States' Policies towards Refugee

and illegal immigrant women)

1.00 – 2.00 PM Lunch break

2.00 – 3.30 PM Participants’ presentation under Module

B (Moderator: Paula Banerjee)

3.30 – 4.00 AM Tea break

4.00

– 5.30 PM Lecture

by OP Mishra, Centre for Refugee Studies, Jadavpur University

6.00

– 7.00 PM Discussion on revision of term papers under Modules A and B with

Ranabir Samaddar and Paula Banerjee and other concerned resource

persons (only with participants presenting papers under these two

modules)

7.00 –

8.00

PM Library hours

5 December (Tuesday)

9.30 – 11.00 AM

Module C/ Oishik Sircar, Pune ILC (The

Politics of Asylum Jurisprudence and International Protection)

11.00

– 11.30 AM Tea break

11.30 –

1.00 PM Module

C/ Parivelan Information Officer TNTRC,

Tamil Nadu

(The Need for National Legislation and Regional Convention for Refugees

and other Victims of Forced Migration)

1.00 – 2.00 PM Lunch break

2.00 – 3.30 PM Participants’ presentation under Module C (Moderator: Khalid Koser, Deputy Director, Brookings-Bern Project on Internal Displacement, Brookings Institution)

3.30 –

4.00 PM

Tea break

4.00 –

5.30 PM

Module

C / Khalid Koser, (Human Rights Origins of the International Regimes of

Protection of the Victims of Forced Migration)

6.00 –

8.00 PM

Library hours 11.00

– 11.30 AM Tea break

11.30 –

1.00 PM Module

D/ Mario Gomez, Bergh of Foundation, Colombo (Human rights

Commission and the Protection of the IDPs in Sri Lanka)

1.00

– 2.00 PM Lunch break

2.00 – 3.30 PM

Participants’ presentation under Module D (Moderator: Sabyasachi Basu

Ray Chaudhury CRG, Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata)

3.30 –

4.00 PM

Tea break

4.00 –

5.30 PM

Roundtable

on"How Effective are the NHRCs in Protecting the Victims of Forced

Migration?" (Mario Gomez, O.P.Vyas, Khalil Ahmed, Uma Josi,

(Participants) Moderator: Parivelan) in collaboration with the dept of

South and Southeast Asian Studies, Calcutta University.

6.00 – 7.00 PM

Discussion on

revision of term papers under Module C and D with Parivelan and Sabyasachi

Basu Ray Chaudhury and concerned resource persons (only with participants

presenting papers under these modules)

7.00 –

8.00 PM

Library hours

9.30 – 11.00 AM

Module C/ Khoti Kamanga (Laws

and Displaced Women in Sub-Saharan Africa)

11.00

– 11.30 AM Tea break

11.30 –

1.00 PM

Participant's workshop on "Resources Violence and Displacement" Muhammad

Rafique, Judith Machhi, Mostafa Mahmud Naser, Saba Hussain, Nir Dahal, Nanda

Kishor, Ksenia Glebova, (Participants) (Moderator: Sabysachi Basu Rao Chaudhury)

1.00

– 2.00 PM Lunch break

3.30 –

4.00 PM Tea break

4.00 –

5.30 PM Camp

life and Voices of Refugees, Ranabir Samaddar and Paula Banerjee

6.00 –

8.00 PM

Library hours

8 December (Friday)

9.00 – 9.30 AM

Briefing

on field visit-Subhas Ranjan Chakraborty, President CRG and Sudeep

Basu, Institute of Development Studies, Kolkata

9.30 – 11.00 AM

Module

D/ Pradip Phanjoubam, Imphal Free Press (Hundred Years of

Displacement in Manipur)

11.00

– 11.30 AM Tea break

11.30 –

1.00 PM

Participant's workshop on "Forced Displacement in Northeast" Pradip

Phanjoubam, Meghna Guhathaurta, Dhaka University and RIB, Dhaka,Madhumita

Sengupta, Dilip Gogoi, Hina Shahid, Jason Miller, S.Y. Surendra Kumar,

(Participants) (Moderator: Samir Kumar Das)

1.00

– 2.00 PM Lunch break

3.30 –

4.00 PM Tea break

4.00 –

5.30 PM Interactive

session with Sohini Ghosh, filmmaker,Jamia Milia Islamia

6.00 –

8.00 PM

Library hours

9.30 – 11.00 AM

Film

Show and discussion 11.00

– 11.30 AM Tea break

11.30 –

1.00 PM Film

Show and discussion contd. / Moderator: Sohini Ghosh

1.00

– 2.00 PM Lunch break

3.30 –

4.00 PM Tea break

4.00 –

5.30 PM Two

parallel sessions on Modules E and F (Meghna Guhathakurta and Ranabir

Samaddar)

6.00 –

8.00 PM

Library hours

10 December (Sunday)

9.30 – 11.00 AM

Discussion

on Creative assignments 11.00

– 11.30 AM Tea break

11.30 –

1.00 PM Module

C/D Sabyasachi Basu Roy Chaudhury

1.00

– 2.00 PM Lunch break

11 December (Monday)

Field

Visit and Public Lecture

12 December (Tuesday)

(Field

Visit)

13 December (Wednesday)

12.00 Noon

Lunch 12.30

– 2.30 PM Module

C / Hans-Joachim Hentze, University of Ruhr, Bochum (International Regime

of Refugee Protection)

2.30 –

3.00 PM Tea

break

3.00 – 4.30 PM

Roundtable discussion

on "Is Palestinian Experience a Unique Experience in Refugee

Annals?" Eeva Puumala, Neha Bhat (participants) Sonia Dayan,

University of Paris VII, Ajay Gandhi, Human rights activist and

researcher, McGill University and Hans-Joachim Heintze,

Moderator:Subhas Chakraborty

14 December (Thursday /

Hotel Sojourm)

9.30 - 11.00 AM

Camp

life: Palestinian Experiences / Ajay Gandhi 11.00

– 11.30 AM Tea

break

11.30 –

1.00 PM Module

F / Roundtable on "Humanitarian Institutions and their Task of

Care" Shiva Dhungana, Oluwaniyi, (Participants) (Moderator: Ranabir

Samaddar)

1.00

– 2.00 PM

Lunch break

6.00 PM

Cultural

Evening

15 December (Friday /

Hotel Sojourm)

9.30 - 11.00 AM

Evaluation

(Sojourn Hotel)

5.00 PM

Valedictory Session, Sojourn Hotel (Salt Lake, Sector III, near Salt

Lake Stadium,

Kolkata 700106)

6

December

(Wednesday)

9.30 – 11.00 AM

Module D/ Khoti Kamanga, Lawyer, Coordinator of the Centre for

the Study of Forced Migration-University of Dar es Salaam and Secretary of

the International Association for the study of Forced Migration (IDP

Situation in Africa)

7 December (Thursday)

2.00 – 3.30 PM

Participant's workshop contd.

2.00 – 3.30 PM

Panel Discussion contd.

9 December (Saturday)

2.00 – 3.30 PM

Two parallel sessions on Modules E and F / Meghna Guhathakurta, and Samir

K. Das respectively

8.00 PM

Rail Journey (Field Visit)

Return Journey by train back to Kolkata

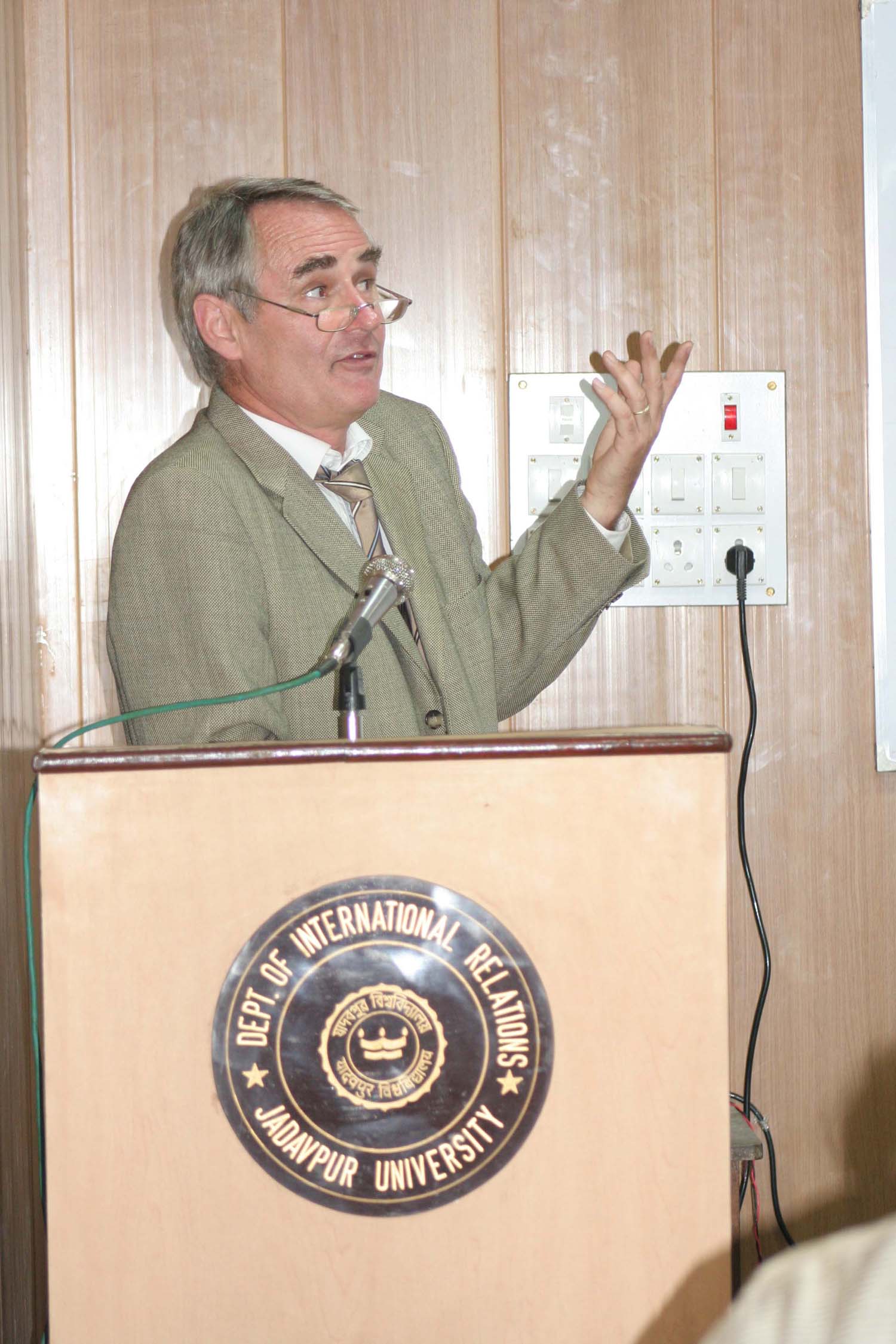

5.00 –

6.30 PM Public

lecture by Dr. Hans-Joachim Heintze in collaboration with the Dept of

International Relations, Jadavpur University, Kolkata

2.00 –

3.30 PM

Rountable Contd.

Presentation of

Certificates

Valedictory Address Hameeda

Hossain, Ain O Kendra, Dhaka on " Forced Migration and Trafficking of

Labour-Migrant Women Workers of Bangladesh"

Vote of

Thanks

Paula Banerjee

Roundtable Discussion in Calcutta University

7. Distance Education, the Modules and Assignments

The course is structured around six modules that have already been mentioned before. The participants are given reading materials on all six modules. The readings are divided in two sections - essential and supplementary. The course material is sent to the participants in a phased manner. The essential readings are sent to them during the distance education period, and the supplementary readings are given when the participants arrive in Kolkata for the direct orientation programme. The essential or core material is in many forms: books, and electrically sent material in form of attachments, CD, and web-posted and web-linked material. The supplementary materials included essays and book sections meant strictly for classroom, journals, are relevant web based materials. Some of the reading material is provided free of cost and some has to be bought by the participants at heavily subsidised rates.

The distance segment of the orientation course begins from 15 September. By 30 September most participants get the books and the module notes. An introductory note on each module is sent to the participants; along with these notes, lists, bibliographies, and other announcements are also sent. Introductory notes are considered extremely useful by the participants as they discussed the modules at some length. The abstracts of these Introductory notes to the modules are given below:

Module A (Forced

Migration,racism,immigration,and xenophobia)

core faculty member: Ranabir Samaddar

The first module deals with linkages between the phenomenon of forced migration and those of racism, xenophobia, and immigration.

While international law on protection of refugees deals with the condition, status, and the rights of persons who have already escaped the persecution and crossed the border to seek asylum, this module deals with what may be called the “root causes” of the flight. It is in this respect that we have to discuss the phenomena of racism and xenophobia, and the relation of the state controls on immigration with the issue of protection of refugees.

Also it must be borne in mind that whatever be the cause, refugees have a right to care, protection, and settlement, though it is true that if the root causes are not considered seriously, then there is a probability that we shall consider the refugee situation as a banal one, and neglect thereby the question of the rights of the refugees or the duty of the States and the international community to protect the escapees of violence. One example is around the concept of “well-founded fear” which is a test for grant of refugee status.

The “well-founded

fear” concept has evolved from a relatively simple inquiry within which the

refugee's subjective feelings of "terror" were prominent, to a much more complex

and wide-ranging inquiry within which concepts such as the "safe state" have

become increasingly the sole determinants of the issue of the well-founded fear.

Or

take this case, on which a jurist had to comment, “Refugee determination

procedure on individual basis and the unequal sharing of burden of care have now

produced confused, traumatized, and nervous shelter-seekers who travel rarely

with supportive documents, false or no papers, and land in alien systems which

are frequently hostile or incredulous" hosts”. In this case involving a Sri

Lanka Tamil who had fled persecution allegedly at the hands of the LTTE (R. SSHD

ex parte Karunakaran 25 January 2000, unreported), the judge commented, “The

civil standard of proof, which treats anything, which probably happened, is part

of a pragmatic legal fiction. It has no logical bearing on the assessment of the

likelihood of future events or (by parity of reasoning) the quality of past

ones... The method of evaluation is itself not one of hard facts. But it

requires knowledge not only of applicant's own tale, and what is accepted of it,

but a whole range of other factual matters.”

In any case, the dual phenomena of racism and

xenophobia have become almost universal phenomena. Xenophobia is a related

phenomenon; aggressive attitude towards national differences produces neo-racist

differences. It had been so earlier also. Partition of states produces the most

concentrated violence, reshaping states reshape minds, and the formation of new

states happens amidst mass murders, mass dislocations, and mass displacements.

Partition refugees are a special category, for they lose the right to return

even a right granted at least nominally to other groups of refugees.

The right to return is

a significant issue in this context. Although much debated internationally

the right to return is most clearly enshrined in the 1966 International Covenant

on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) under its provisions on the right to

freedom of movement (Article 12.4) which says that No one shall be arbitrarily

deprived of the right to enter his own country. But this right has often

proved to be a chimera at least in South Asia. A historian has shown that

perhaps the first group of people, though not refugees, whose right to

return was denied by a South Asian state were the Indian emigrants who travelled

abroad in the nineteenth century to work as plantation labourers. All through

the nationalist period the fate of these labourers in their country of domicile

was a rallying point for Indian leaders to portray the dark side of foreign

rule. There was constant reiteration that the state was responsible for all the

people who were born in India. Yet during the legislative assembly debates in

1944 the leaders came to a consensus that these émigrés rightfully belonged to

their country of domicile and not in India. Unlike nationalists during the

colonial period, the leaders of the post-colonial State formation project no

longer looked forward to the return of the emigrants who were slowly being

considered as foreigners. South Asian independence was accompanied by a

blood bath. The partition of India and Pakistan resulted in two million deaths

and about 15 million people were displaced. Most of the refugees were lucky

enough to get domicile and often citizenship in their country of domicile. Yet

problem arose over the issue of return. South Asian states passed legislations

whereby property of the displaced were confiscated by the State and treated as

enemy property. So the home that they wanted to go back to remained only

in their own imagination. One often hears the argument that because partition

refugees got an alternate citizenship they lost the right to return. In South

Asia there are however, other groups of refugees who remain as stateless people;

yet they are denied the right to return. We have the instances of two such

groups of refugees: the Chakmas (Jumma people) and the Bhutanese. The focus in

any discussion on the right to return of citizens expelled has to be thus on the

need to move away from the classical theories of sovereignty, democracy, State,

and citizenship, and take the exile, the alien, the displaced (both internally

and trans-border), and the half-citizen as the central figure of the politics in

South Asia, the figure who is with us like the eternally accompanying shadow, so

normalised that we forget its existence which we have taken for granted. In this

physical milieu of expulsion, de-enfranchisement, and nationalisation, the right

to return is at once the most crucial question and the most hallucinatory claim.

The last point that

this module discusses is the relation between refugee flow

immigration flow, and the way

these flows mix to form

massive and mixed flows of population groups in today's world.

Module A is the

beginning. But the module should offer enough glimpses of the problems in the

issue of refugee protection today, so that the following modules in this course

can be appreciated better. And, one must not forget that in all instances and

phenomena cited above gender stays as the most deeply inscribed category of

discrimination and difference, if discrimination and difference are taken as the

key opening words. A good beginning means an anticipation of the problems that

will arise at the end.

References

Etienne Balibar, in Etienne Balibar and Immanuel Wallerstein, Race, Nation, Class – Ambiguous Identities (Verso, 1991)

B.S. Chimni, International Refugee Law – A Reader (Sage Publications,

2003), section 5

Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Peace Studies I (Sage Publications, 2004),

chapters 7-8, 13-14

Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Refugees and the State (Sage Publications, 2003),

chapters 1-3, 6, 9

Ranabir Samaddar, The Marginal Nation (Sage Publications, 1999), chapters

1-4, 13

REFUGEE WATCH, “Scrutinising the Land Settlement Scheme in Bhutan”, No. 9, March

2000

REFUGEE WATCH, “Displacing the People the Nation Marches Ahead in Sri Lanka”,

No. 15, September 2001

Web-based

RW.: Displacing the People the Nation Marches Ahead in Sri Lanka http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch15_7.htm

RW.: Mohajirs : The Refugees By Choice http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch14_5.htm

TERM

PAPER

MODULE

A

Forced Migration,racism,immigration,and xenophobia

Write a note on how the syllabus and the reading material of this course connect the four key words of this module - forced migration, racism, immigration, and xenophobia - and build on the basis of these linkages an orientation course on forced migration.

OR

Prepare and present a fact sheet of newspaper reports (4 pages) on an event or topic related to any of the four themes mentioned in the title of the module and show thereby how a refugee situation or that of internal displacement is created.

OR

Discuss with the help of case studies the various elements involved in the "right to return" and argue in the context of those elements if the right to return can be considered as a substantive one or otherwise.

OR

Write a note on the context of the phrase, "mixed and massive flows" of migration, and show how this situation affects the task of protecting the refugees.

Module B (Gender

dimensions of forced migration, vulnerabilities, and justice)

core faculty member: Paula Banerjee

Over one percent of

the total world population today consists of refugees. More than eighty

percent of that number is made up of women and their dependent children.

An overwhelming majority of these women come from the developing world. South

Asia is the fourth largest refugee-producing region in the world. Again, a

majority of these refugees are made up of women. The sheer number of women among

the refugee population portrays the gendered nature of the issue. The nation

building projects in South Asia has led to the creation of a homogenised

identity of citizenship. State machineries seek to create a “unified”

and “national” citizenry that accepts the central role of the existing

elite. This is done through privileging majoritarian, male and monolithic

cultural values that deny the space to difference. Such a denial has often

led to the segregation of minorities, on the basis of caste, religion and gender

from the collective “we”. One way of marginalising women from body politic

is done by targeting them and displacing them in times of state verses community

conflicts. As a refugee a woman loses her individuality, subjectivity,

citizenship and her ability to make political choices. As political

non-subjects refugee women emerge as the symbol of difference between citizens

and its other: the refugees and the non-citizens. By taking some select examples

from South Asia in this module we will address such theoretical assumptions.

Here the category of refugee women will include women who have crossed

international borders and those who are internally displaced and are potential

refugees.

References

Paula Banerjee, Sabyasachi Basu Ray

Chaudhury and Samir Das, Internal Displacement in South Asia, chapter 9.

B.S. Chimni, International

Refugee Law – A Reader (Sage Publications, 2003), section 1

Ritu Menon and Kamla Bhasin,

Borders and Boundaries, chapter 3.

Joshva Raja, Refugees and their

Right to Communicate, chapter 8.

Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Refugees

and the State (Sage Publications, 2003), chapter 9.

Ranabir Samaddar, The Marginal

Nation (Sage

Publications, 1999), chapter 12.

Refugee Watch, Nos. 10-11

UNHCR Policy on Refugee Women

Select UNICEF

Policy Recommendation on the Gender Dimensions of Internal Displacement

http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch10&11_92.htm

CEDAW :

http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/econvention.htm

RW.: Dislocated Subjects : The Story of Refugee Women

RW.: War and Its Impact on Women in Sri Lanka

RW : Afghan Women In Iran

RW.: Refugee Women of Bhutan

RW.: Rohingya Women – Stateless and Oppressed in Burma

RW.: Dislocating the Women and Making the Nation

TERM PAPER MODULE

B On

the basis of a close reading of B.S. Chimni's Reader address the debate: is it

desirable that women be treated as a separate legal category in international

and national legal regimes of protection. OR Compare

the situation of Sri Lankan women IDPs and Afghan refugee women in Pakistan. OR Why

listening to women's experiences and chronicling them is particularly relevant

for understanding refugee situations in South Asia. OR In

the context of women's displacement all over South Asia discuss women's lack of

control over institutional structures of protection. OR Is

lack of control over resources a reason for women's displacement? Argue

your case with reference to one particular group of women refugees/IDPs.

Module C (International,

regional, and national regimes of protection)

Module C deals with the international and national legal regimes of protection

of the victims of forced displacement and their right.

Refugee Law is a relatively new branch of International Law. The first major

step towards developing an international regime of protection was the 1951

Convention that was later modified by the 1967 Protocol. From then on the 1951

convention has formed the core of all Human Rights Law and Humanitarian Law for

the protection of refugees. The 1951 Convention defines a refugee as a person

who owing

to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion,

nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is

outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is

unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having

a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as

a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to

return to it.

However since its inception there have been many objections to the provisions of

the 1951 convention. It is said that the Convention mandates protection for

those whose civil and political rights are violated, without protecting persons

whose socio-economic rights are at risk. Also it has been criticised on the

grounds of its Euro centrism, and insensitivity towards the internecine racial,

ethnic and religious conflicts in third world, which has resulted in the

creation of refugees in large numbers. The provisions of the convention have

served well for the protection of refugees during the Cold War times but have

failed to do so after that. Today the first world often attempts at dealing

with the refugee problems ‘at source’. This has led to the international

interference in the internal matters of a sovereign nation creating further

problems for states and for the displaced. This has been witnessed very recently

in the Darfur region of Sudan and in past in former Yugoslavia, Somalia, and

other African countries.

Today

provisions of the 1951 Convention seems dated and in need for further revision

due to increased complexities in the process of refugee generation, protection

and also due to advances in the field of refugee studies. The increased focus on

refugee studies has led to broadening of definitions of ‘refugee’, ‘protection’,

‘rights’, ‘justice’ etc. As a result of all these reasons the 1951 Convention

has not been ratified by many nations of the world. Many regions have developed

its own regimes for protection of people facing forced displacement. The OAU

Convention expanded the definition of refugee contained in the 1951 Convention.

The OAU Convention defines the term “refugee” to include persons fleeing their

country of origin due to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination, or

events seriously disturbing public order in either a part or the whole of the

country of origin or nationality. This implies that “well-founded fear” is a

subjective category and anyone facing civil and political disturbances and war

need not prove their well-founded fear for life. The Cartagena Declaration

recommends a definition similar to that contained in the OAU Convention. In so

far as Asia is concerned mention may be made of the Asian African Legal

Consultative Committee (AALCC) in 1966. But this has not had the impact of

either the OAU Convention or the Cartagena Declaration. South Asia has not been

able to develop a legal regime for refugees or IDPs.

In

this module we have focusses on the various aspects of refugee protection at an

international level in general and on South Asian level in particular (Module D

discusses in details the legal principles of protection of IDPs).

Paula

Banerjee, Sabyasachi Basu Ray Chaudhury and Samir Das, Internal Displacement

in South Asia, Epilogue

F-e-material 1 – International Humanitarian Law and

Human Rights Law

Convention Against Torture

REFUGEE

WATCH

TERM PAPER MODULE

C

The partition of the

Indian subcontinent in 1947 witnessed probably the largest refugee movement in

modern history. About 8 million Hindus and Sikhs left Pakistan to resettle

in India while about 6-7 million Muslims went to Pakistan. Such transfer

of population was accompanied by horrific violence. Some 50,000 Muslim

women in India and 33,000 non-Muslim women in Pakistan were abducted, abandoned

or separated from their families. Women's experiences of migration, abduction

and destitution during partition and State's responses to it is a pointer to the

relationship between women's position as marginal participants in state politics

and gender subordination as perpetrated by the State. In this context the

experiences of abducted women and their often forcible repatriation by the State

assumes enormous importance today when thousands of South Asian women are either

refugees, migrants or stateless within the subcontinent. Abducted women

were not considered as legal entities with political and constitutional rights.

All choices were denied to them and while the state patronised them verbally by

portraying their “need” for protection it also infantilised them by giving

decision making power to their guardians who were defined by the male pronoun

“he”. Even today the refugee women do not represent themselves.

Officials represent them. For the abducted women it was their sexuality

that threatened their security and the honour of the nation.

Refugee women from

other parts of South Asia reflect trauma faced by women belonging to communities

considered as disorderly by the state. During multiple displacements women who

have never coped with such situations before are often at a loss for necessary

papers. When separated from male members of their family they are

vulnerable to sexual abuse. The camps are not conducive for the personal safety

of women, as they enjoy no privacy. But what is more worrying is that

without any institutional support women become particularly vulnerable to human

traffickers. These people aided by network of criminals force women into

prostitution. Millions of rupees change hands in this trade and more lives

get wrecked every day. Many displaced women who are unable to cross

international border swell the ranks of the internally displaced. Even in IDP

camps women are responsible for holding together fragmented families.

Today roughly one-third of all households in Sri Lanka are headed by women and

the numbers increase many fold in the camps for internally displaced.

Although 89 percent women in Sri Lanka are literate, due to two decades of armed

conflict women from North and East have lower levels of education with one in

every four being illiterate. A report based on a research carried

out at Mannar district portray that among 190,000 IDPs women often find it

impossible to generate enough income for buying food for the whole family.

In Illupakkadavai, all 36 heads of female-headed households stated that they

rely on dry rations for approximately 90 percent for their nutritional needs and

that the children of women headed households are most vulnerable to

exploitation. In Sri Lanka suicide rates for women have doubled in the

last two decades.

None of the South

Asian states are signatories to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of

Refugees or the 1967 Protocol. As India is the largest South Asian state

it should be interesting to see how women refugees are dealt with here. In

India Articles 14, 21 and 25 under Fundamental Rights guarantees the Right to

Equality, Right to Life and Liberty and Freedom of Religion of citizens and

aliens alike. Like the other South Asian states India had ratified the

1979 Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women

in 1993. Although there is no incorporation of international treaty

obligations in the Municipal laws still rights accruing to the refugees in India

under Articles 14, 21 and 25 can be enforced in the Supreme Court under Article

32 and in the High Court under Article 226. The other guiding principles

for refugees are the executive orders that have been passed under the Foreigners

Act of 1946 and the Passport Act of 1967. The National Human Rights

Commission has also taken up questions regarding the protection of refugees.

It approached the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the Constitution and stopped

the Expulsion of Chakma refugees from Northeast India. Yet all these orders are

ad hoc in nature and the legal position remains nebulous. This is true not

just of India but all of South Asia.

The overwhelming presence of women among displaced populations is not an

accident of history. It is a way by which states have made women political

non-subjects. By making women permanent refugee, living a savage life in

camps, it is easy to homogenise them, ignore their identity, individuality and

subjectivity. By reducing refugee women to the status of mere victims in

our own narratives we accept the homogenisation of women and their

depoliticisation. We legitimise a space where states can make certain

groups of people political non-subjects. In this module we intend to

discuss the causes of such depoliticisation that often results in displacements.

We will also discuss the situation of displaced women in South Asia and consider

policy alternatives that might help in their rehabilitation and care.

Web-based

http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch10&11_92.htm

http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch10&11_8.htm

http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch10&11_4.htm

http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch10&11_6.htm

http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch10&11_5.htm

http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch10&11_5.htm

http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch17_1.htm

http://www.unifemantitrafficking.org/main.html

Gender

dimensions of forced migration, vulnerabilities, and justice

Core faculty member: Khalid Koser

Another failure of the Convention has been the inability to recognise the

special needs of women, children, and aged people within the sections of

refugees, though this has been addressed to some extent in the provisions of

CEDAW convention. In 1985, the UNHCR Executive Committee adopted Conclusion No.

39 that recognised that refugee women and girls formed a majority among the

world refugee population. The Conclusion also recognised that states were free

to consider women facing inhuman treatment as belonging to a particular social

group within the 1951 convention. In October 1993 the UNHCR adopted Conclusion

No. 73 that stated that all those who have suffered sexual violence should be

treated with particular sensitivity. However, there is little in UNHCR

guidelines that can make women victims of sexual violence as special claimants

for refugee protection.

None

of the South Asian states are a signatory to the 1951 Convention or the 67

Protocol. India has also stayed away from these mechanisms, citing certain

biases in the provisions of the convention. However, it has developed its own

provisions to deal with the problems of refugees on a case-by-case basis in

absence of a consistent national policy. This has its own problems, for example

India has provided all possible help to Tibetan refugee due to its own political

necessities but has not done so with the Bangladeshi and Bhutanese refugees. The

provisions of Indian state has also not progressed with the evolution of

feminist critic of the protection regimes which needs attention and creation of

a consistent policy accommodating the faults in current practices.Not

everyone who applies for refugee status can get protection. In 1951 Convention

there are a list of “exclusion clauses” containing categories of persons who do

not deserve international protection.

References

B.S. Chimni, International Refugee Law – A Reader (Sage Publications,

2003)

Who is a Refugee?, Pgs. 1-81; Asylum, Pgs. 82-160; Rights and Duties of a

Refugee, Pgs. 161-209

Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Refugees and the State (Sage Publications, 2003),

chapters 10-11.

Refugee Watch No.4 (December 1998) articles by Sarbani Sen and Brian Gorlick.

Web-based

Document printed from the website of the ICRC.

URL: http://www.icrc.org/web/eng/siteeng0.nsf/html/57JMRT

International Committee of the Red Cross

CAT:

http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/39/a39r046.htm

International,

regional, and the national regimes of protection

Do you think that the category of "well-founded fear" reflects subjectivity in the definition of refugees as indicated in the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees? Comment in the light of the definition adopted by the OAU Convention.

OR

Examine the principle of non-refoulement in relation to the policy of non-entrée.

OR

Do you think that there is a need for a national law on refugees? Argue your case with reference to experiences of any country.

OR

Explain how the Conclusion No. 39 and 73 adopted by the UNHCR Executive Committee and the CEDAW have attempted to take into account the special needs of women refugees.

OR

How the internally displaced persons can return to the places of their habitual residence and/or resettled? Discuss with special reference to Principles 28 and 29 of the UN Guiding Principles

Module D (Internal

displacement - causes, linkages, and responses)

Core faculty member: Sabyasachi Basu Ray Chaudhuri

The eviction of indigenous people from their land is a recurrent theme in South Asia. Be it Ranigaon, Golai, Motakeda, Somthana, Ahmedabad, Bandarban, or Trincomalee, thousands of families are being evicted from their homes either in the name of conflict or in the name of modernization. They are being forced to stay in the open, in pouring rain with a number of them suffering from malnutrition and starvation and they are fearful for their lives at most times. The last two decades have witnessed an enormous increase in the number of internally displaced people in South Asia. Their situation is particularly vulnerable because unlike the refugees they are unable to move away from the site of conflict and have to remain within a state in which they were displaced in the first place. These unfortunate people who have been displaced once are often displaced multiple times by the hands of the powers that be. Yet as displaced they do not have the capacity to cross international borders but seek rehabilitation from the powers that are responsible for their displacement in the first place.

The situation of the internally displaced persons (IDPs) seems particularly vulnerable when one considers that there are hardly any legal mechanisms that guide their rehabilitation and care in South Asia. Since the early 1990s the need for a separate legal mechanism for IDPs in South Asia has increasingly been felt. This is not only to compile new laws but also to bring together the existing laws within a single legal instrument and to plug the loopholes detected in them over the years. Only recently the international community has developed such a mechanism that is popularly known as the UN Guiding Principles on internal displacement. This has given us a framework within which rehabilitation and care of internally displaced people in South Asia can be organised. Keeping that in mind it becomes imperative for scholars working on issues of forced migration in South Asia to consider whether South Asian states have taken the Guiding Principles into account while organising programmes for rehabilitation and care for the internally displaced persons (IDPs).

The Guiding Principles on Internally Displaced Persons set out the rights of internally displaced persons relevant to the needs they encounter in different stages of displacement. The Guiding Principles provide a handy schematic of how to design a national policy or law on internal displacement that is focused on the individuals concerned and responsive to the requirements of international law. Similarly, governments (and particularly national human rights institutions where they exist), advocates, and displaced persons can use the Guiding Principles as a means to measure the compliance of existing laws and policies with international standards. Finally, their simplicity allows the Guiding Principles to effectively inform the internally displaced themselves of their rights. The Guiding Principles are thus part of a growing number of “soft law” instruments that have come to characterize norm-making in the human rights field as well as other areas of international law, in particular environmental, labor and finance.

The

short notes to the questions presented below indicate the discussions that this

module aims to discuss.

What Types of Displacement are Prohibited by the Guiding Principles?

Principle 6 affirms that “[e]very human being shall have the right to be protected against being arbitrarily displaced from his or her home or place of habitual residence.” Support for this proposition can be found in humanitarian law and also in the right to movement, guaranteed by a number of human rights instruments, which can be reasonably expected to have as its corollary the “right not to move.” Where displacement is to occur outside the context of armed conflict, Principle 7 provides a list of procedural protections that must be guaranteed, including decision- making and enforcement by appropriate authorities, involvement of and consultation with those to be affected and the provision of an effective remedy for those wishing to challenge their displacement. These provisions are, of course, of particular interest to those facing displacement for development projects.Moreover, in either context, “all measures” must be taken to minimize the effects and duration of the displacement and the responsible authorities are required to ensure “to the greatest practicable extent” that the basic needs of those displaced (e.g., shelter, safety, nutrition, health, and hygiene) are met. It should also be noted that Principal 9 articulates a “special obligation” to protection against displacement of a number of groups whose special attachment to territory has been recognized in international law, including indigenous persons, minorities, peasants, and pastoralists.

What Rights do Persons have once Displaced?

Displaced persons enjoy the full range of rights enjoyed by civilians in humanitarian law and by every human being in human rights law. These include the rights to life, integrity and dignity of the person (e.g., freedom from rape and torture), non-discrimination, recognition as a person before the law, freedom from arbitrary detention, liberty of movement, respect for family life, an adequate standard of living (including to access to basic humanitarian needs), medical care, access to legal remedies, possession of property, freedom of expression, freedom of religion, participation in public life, and education, as set out in Principles 10-23.In several instances, the Guiding Principles specify how generally expressed rights apply in situations of displacement. These should be of particular interest to those designing and assessing domestic policies on internal displacement. For example, Principle 12 provides that, to give effect to the right of liberty from arbitrary detention, internally displaced persons “shall not be interned in or confined in a camp” absent “exceptional circumstances” and that they shall not be subject to discriminatory arrest “as a result of their displacement.” Likewise Principle 20 provides that the right to “recognition everywhere as a person before the law” should be given effect for displaced persons by authorities facilitating the issuance of “all documents necessary for the enjoyment and exercise of their legal rights, such as passports, personal identification documents, birth certificates and marriage certificates.” The Guiding Principles provide for special consideration of the needs of women and children (including “positive discrimination” or affirmative activities on behalf of governments to model assistance and protection to their particular needs, consultation and involvement in decisions regarding their displacement and return or resettlement, protection against recruitment of minors and free and compulsory education), as well as for other especially vulnerable groups, such as the elderly and disabled.

What Help Should Displaced Persons Expect with Return, Reintegration and Resettlement?

The Guiding Principles provide that competent authorities have “the primary duty and responsibility” to assist displaced persons by providing the means as well as by establishing conditions for return to their places of origin, or for resettlement in another part of the country (Principle 28). Any return or resettlement must be voluntary and carried out in conditions of safety and dignity for those involved. As a corollary to the right to free movement, therefore, displaced persons have the right to return to their homes. Although the right to return or resettle is not expressly stated in any particular human rights instrument, this interpretation of the right of free movement is strongly supported by resolutions of the Security Council, decisions of treaty monitoring bodies, and other sources of authority. However, though the displaced have the right to return, Principle 28 carefully specifies that they must not be forced to do so, particularly (but not only) when their safety would be imperiled. The issue of the voluntariness of return or resettlement is recurrent in protracted displacement situations around the world. In many places, governments and insurgent groups have ceded to the temptation to use the return or resettlement of displaced persons as a political tool.

Are their any special provisions for women?